|

|

|

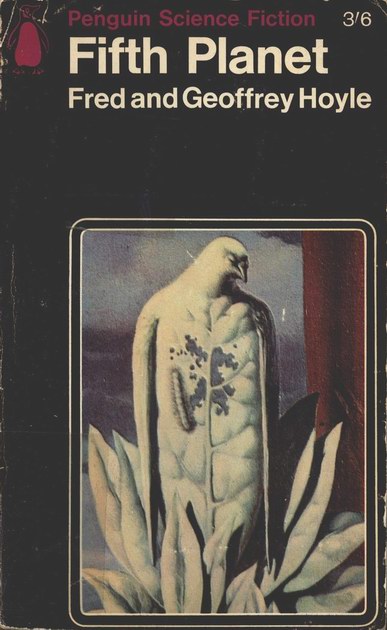

Penguin Science Fiction 2244 Fifth Planet Fred Hoyle, F.R.S., well known as an astronomer, His other publications include The Nature of the Born in 1942, Geoffrey Hoyle is Fred Hoyle's son. |

| {2} |

|

Fifth Planet Fred Hoyle and Geoffrey Hoyle

|

| {3} |

Penguin Books Ltd, Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, Ringwood, Victoria, Australia

First published by William Heinemann Ltd 1933

Published in Penguin Books 1965

Reprinted 1967

Copyright © F. and G. Hoyle, 1963

Made and printed in Great Britain by Cox & Wyman Ltd; London, Reading and Fakenham Set in Intertype Baskerville

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

| {4} |

The very nature of the plot has forced us to set this story in the more distant future than we would otherwise have preferred. It is hardly possible to foresee the shape of society a century or more ahead of one's own time, and we have not attempted to do so. Instead we have been content to extrapolate those social trends that can plainly be seen at the moment. The story was written in August 1962. We mention this to bring out the prediction — we take a little pride in its apparent correctness — at the foot of page 22. We do not know whether to hope or fear that other predictions of the story will turn out to possess a similar validity.

The basis of the plot is to be found on pages 208 to 210. However, to avoid too much interruption of the narrative, the ideas mentioned in these pages have been shortened as far as possible. Physics regards the world as four dimensional. All moments of time exist together. The world can be thought of as a map, not only spatially, but also with respect to time. The map stretches away both into the past and into the future. There is no such thing as ‘waiting’ for the future. It is already there in the map.

Two problems arise out of this. The first is the so-called ‘arrow of time'. Events occur in the map in definite sequences. Light emerges from a torch after you press the switch. The emphasis here is not on the word ‘after’ — it would be possible to turn the map round, to count time backwards, as we do in counting years B.C. Then one would say that light emerges from the torch before one presses the switch. This is simply a trivial inversion. What is not trivial is that light does not emerge both before and after the pressing of the switch. {5} Events do not occur symmetrically with respect to time. In the case of the torch there is an asymmetry whichever way we elect to read the map. It is this asymmetry that we refer to as the arrow of time. The ‘future’ part of the map is radically different from the ‘past’, and this is true whichever way we turn the map.

Physics has made a good deal of progress in understanding this problem. The arrow of time may not be completely resolved, but at any rate it is being grappled with. The same cannot be said for the second problem.

What constitutes the present? Provided one considers oneself as something apart from the physical world, the answer does not seem difficult. The present can be thought of as the particular place in the map where you happen to be. It is your subjective presence at a particular spot that defines the present. But you cannot have your cake and eat it. You cannot consider your subjective presence as being outside the physical world and in the same breath consider yourself as a part of the map.

According to science, a human is an animal. He takes his place in the map along with all other physical events. In fact the events that constitute the human are confined to a four-dimensional tube, a world tube, that threads its way over a finite portion of the map. What then is the subjective present? It is certainly not the whole collection of events inside one's own personal tube, otherwise we should live the whole of our lives all at once, like playing a sonata simply by pressing the whole keyboard. Stated more precisely, the subjective present consists not of the complete collection of events but of a certain subset. How is the subset defined?

Certain clear technical issues now appear. Is the subset such that one particular member has a time-like displacement to all other members? In that case the other members could have a causal connexion to the particular member. But if so, how is the particular member of the subset chosen?

There seems to be no way of coping with issues such as these except by admitting that something else besides the {6} four-dimensional world tube is needed. Something else outside what science would normally describe as the animal itself.

This approach need not be mystic. The required subset could be defined mathematically as the intersection of the world tube with a three-dimensional space-like surface. Thus a surface

φ(x1, x2, x3, x4) = c

for a particular value of c, and with ∂φ/∂xi (i = 1,2,3,4) a time-like vector, serves to define a subset of points in the world tube. Changing c changes the subset. We could be said to live our lives through changes of c — i.e. by sweeping through a family of surfaces.

It is plausible that the subjective present has a mathematical structure of this kind. But what then are the φ surfaces? Could they be derived from known physical fields, for example from the electromagnetic field? That is to say, is the subjective present really controlled by normal sensory,data? An obvious way of testing this possibility would be to keep the known external fields constant and to consider whether the subjective present can be considered to change.

Our impression — no more than an impression — is that changes of the subjective present do occur under conditions where the external electromagnetic field, for example, is essentially unchanged. As a rather imprecise example of what we mean, suppose two visits separated by many years are made to a particular place — say, to a mountain — and suppose the weather and the lighting conditions are generally similar on the two occasions. Exact identity of condition is of course impossible, but we find it difficult to believe that major differences of the subjective present, such as might be felt by an individual, are determined by slight, and perhaps even unnoticed, changes in the external conditions — e.g. by the slight shift in the disposition of grass and boulders on a mountainside.

The φ surfaces we feel must have the property of not being {7} closely reproducible in the sense of this example. The fantasy of the present story lies in the properties we have ascribed to these surfaces, in fact to the functional behaviour of φ.

6 April 1963 |

F. H. |

| {8} |

1 | |

2 | |

3 | |

4 | The Rocket 36 |

5 | Personnel 45 |

6 | |

7 | |

8 | The Voyage 80 |

9 | The Landing 95 |

10 | Exploration 114 |

11 | The Return 138 |

12 | Dulce Domum 150 |

13 | Cathy 162 |

14 | War 178 |

15 | The Aftermath 193 |

| {9} |

If you have enjoyed reading this book you may wish to know that Penguin Book News appears every month. It is an attractively illustrated magazine containing a complete list of books published by Penguins and still in print, together with details of the month's new books. A specimen copy will be sent free on request.

Penguin Book News is obtainable from most bookshops; but you may prefer to become a regular subscriber at 3s. for twelve issues. Just write to Dept EP, Penguin Books Ltd, Harmondsworth, Middlesex, enclosing a cheque or postal order, and you will be put on the mailing list.

Another Penguin by Fred Hoyle is described overleaf.

Note: Penguin Book News is not available in the U.S.A., Canada or Australia

| {222} |

Fred Hoyle

In 1964, a cloud of gas, of which there are a vast number in the universe, approaches the solar system on a course which is predicted to bring it between the Sun and the Earth, shutting off the Sun's rays and causing incalculable changes on our planet.

The effect of this impending catastrophe on the scientists and politicians is convincingly described by Fred Hoyle, the leading Cambridge astronomer: so convincingly, in fact, that the reader feels that these events may actually happen. This is science fiction at its very highest level.

‘The Black Cloud is an exciting narrative, but, far more important, it offers a fascinating glimpse into the scientific power-dream’ — Peter Green in the Daily Telegraph

‘Mr Hoyle has written a really thrilling book . . . There is a largeness, generosity, and jollity about the whole spirit of the book that reminds one of the early Wells at his best’ — New Statesman

‘. . . The imagination is touched by this desperate effort by man to regain control of his environment by using his knowledge and his wits’ — The Times Literary Supplement

‘Mark: Alpha’ — Maurice Richardson in the Observer

NOT FOR SALE IN THE U.S.A.