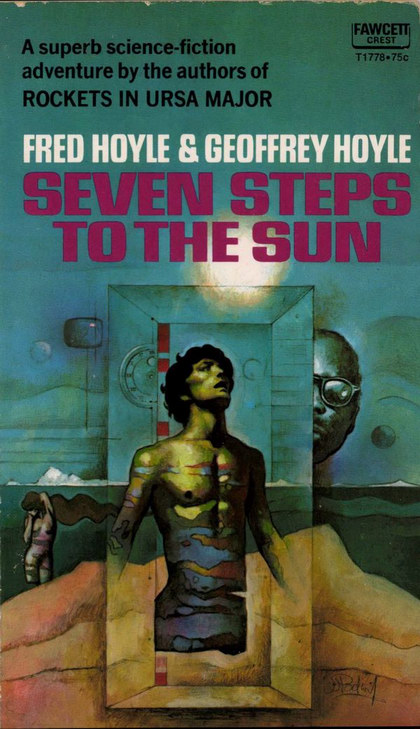

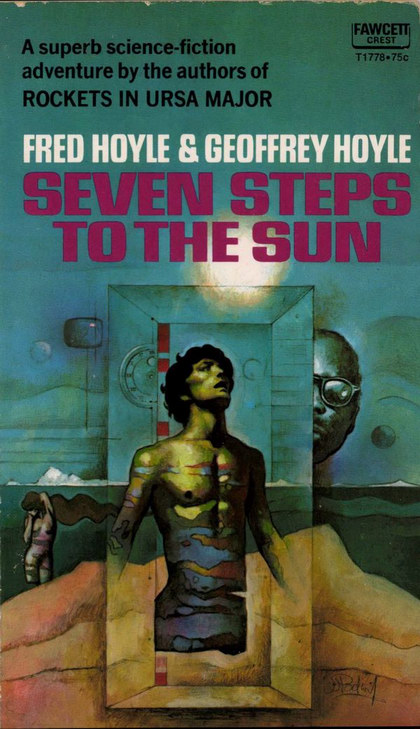

Seven Steps

to the Sun

| {1} |

Fawcett Crest Books

by Fred Hoyle:

OCTOBER THE FIRST IS TOO LATE

ROCKETS IN URSA MAJOR (with Geoffrey Hoyle)

SEVEN STEPS TO THE SUN (with Geoffrey Hoyle)

|

Are there Fawcett paperback books YOU WANT BUT CANNOT FIND IN YOUR LOCAL STORES? You can get any title in print in Fawcett Crest, Fawcett Premier, or Fawcett Gold Medal editions. Simply send title and retail price, plus 15tf to cover mailing and handling costs for each book wanted, to:

Books are available at discounts in quantity lots for industrial or sales-promotional use. For details write FAWCETT WORLD LIBRARY, CIRCULATION MANAGER, FAWCETT BLDG., GREENWICH, CONN. 06830 |

| {2} |

Seven Steps

to the Sun

by FRED HOYLE & GEOFFREY HOYLE

A FAWCETT CREST BOOK

Fawcett Publications, Inc., Greenwich, Conn.

| {3} |

For GRAM

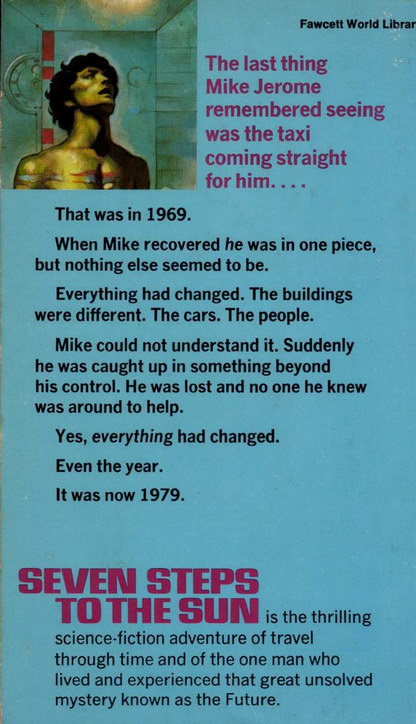

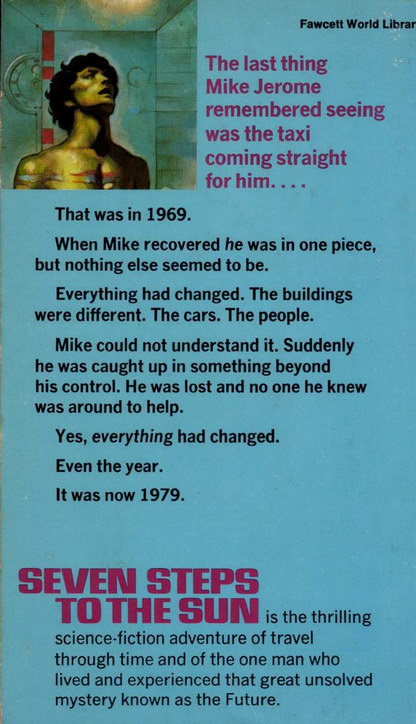

SEVEN STEPS TO THE SUN

THIS BOOK CONTAINS THE COMPLETE TEXT OF THE ORIGINAL HARDCOVER EDITION.

A Fawcett Crest Book reprinted by arrangement with Harper & Row Publishers

Copyright © 1970 by Fred Hoyle and Geoffrey Hoyle.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form.

All the characters in this book are fictitious, and any resemblance to actual persons living or dead is purely coincidental.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 73-138786

Printed in the United States of America

January 1973

| {4} |

‘I never think of the future. It comes soon enough.’

Einstein

HOT still air hung over the evening rush hour as Mike Jerome walked wearily from the dubbing studio. He stood on the edge of the pavement in Bayswater Road jaded by thoughts of the immense amount of writing he'd put into this film. Distracted by a girl among the rush hour travellers he was reminded vividly of Sue — she'd not been in touch since their bitter parting in New York. Still he wasn't unhappy. Just tired. An empty cab appeared and he moved quickly into the road flailing his arms. The driver manoeuvred his vehicle deftly from the outside lane.

‘47 Frith Street,’ said Mike, as he settled back.

His mind wandered over the petty events that led up to the quarrel with Sue. She'd wanted to stay on in New York, where she could enjoy her new found friends, while he battled with the television and film people to get some work. He wouldn't have minded, as he liked New York, but it was obvious Sue was interested in one of the men she'd met, and he didn't intend spending vast sums of his hard-earned money feathering her nest to share with someone else. The row had been short, sharp and final. Since he'd started working on this film his tolerance level had dropped almost to zero. The flat was a bit of a problem with too much in it reminding him of her.

The taxi suddenly pulled up with a jolt; he was outside 47 Frith Street. Descending the stairs of the building to the basement door, he pushed it open and went into the jazz club. A moment or two and his eyes grew accustomed to the dim light. Standing up against the bar was the vast dark form of Pete Jones. Mike had met Pete some ten years before in Paris, when Pete was studying music at the Sorbonne, and he himself had been picking up spare cash by playing jazz piano in a club. From those very early days in Paris they had remained close friends.

‘How'd it go, man?’ asked Pete as Mike approached the bar. {5}

‘So, so.’

‘Drink?’

‘Thanks, when did you start?’

‘Around ten, ten thirty,’ came the bored reply.

‘Idiot, when did you start boozing?’ asked Mike.

‘I think I must have been about six months old. My mother used to get me tight so that I wouldn't cry while I was teething, ever since then I've been addicted.’

‘It must be about time someone put food in that stomach, then.’

Pete's face lit up. ‘You're paying?’ he said, as the two men finished their drinks and started to leave the club.

‘You know, one of these days I'll drop dead with your generosity,’ said Mike.

‘Where to?’ Pete asked, taking no notice of the heavy traffic as he crossed Shaftesbury Avenue against the lights.

‘Wheeler's; it's fish night.’

They made their way through crowded Soho to Old Compton Street.

There wasn't a table ready, so they deposited themselves in the bar with two large whiskys.

‘Got rid of her junk yet?’ asked Pete, draining his glass in one go.

‘No, but I'll get around to it.’

‘Good, you're well clear of that bitch.’

‘Right all along!’

‘Well, now that that relationship's over, who's next?’ asked Pete, with a big hearty chuckle.

‘Got any ideas?’ Mike grinned suddenly.

He remembered the nights they'd spent on boulevard St. Germain, looking for talent in cafes. Usually they'd spend a fortune, or what seemed like a fortune, buying likely young women drinks, only to find themselves almost invariably cut off without any return on their investment. At these times, Pete would shake his head, sigh, and say with relish, ‘Well, now that that relationship's over, who's next?’ They would count up their remaining few francs and start again.

Pete ordered more whisky and looked thoughtfully at his friend.

‘Man, what's bothering you?’

‘This,’ said Mike quietly banging his head with his hand. ‘I'm so tired I don't really have much idea of what I'm doing.’

‘Take a break,’ urged Pete sternly.

‘I can't, I've got this television programme to write.’ {6}

‘Drop it.’

‘Can't afford to; it'll be a stopgap until the film comes out. Then if everything goes, I'll be able to do what I want to.’

‘Maybe, but it'll be no use to you if you're ill, or dead from a heart attack.’

‘Well, I'm not; and if you were in the same position you'd do the same.’

‘Sure, but you don't use anything to keep you going,’ said Pete.

‘No. I've seen enough of you under the influence of drugs and drink not to want them.’

‘O.K., so go to a doctor, and see what he can do for you.’

‘Why waste the money? I know what they'll say. Take a holiday.’

‘Well, whatever you say, Mike, I still think you need something to keep you from walking under a bus.’

Mike stretched out wearily. ‘There is something I could do with, and that's a good massage, to iron out some of the aches and pains.’

‘That's a great idea. There's a girl in Harley Street. Don't know how good she is at body rubbing, but she looks fabulous,’ said Pete with an evil grin.

‘What's her name?’

‘Couldn't tell you. She was in the club some time ago. You know, a little over-enthusiastic, talked to me most of the evening and then said she worked in Harley Street, and any time I wanted a rub down, to go along.’

The restaurant manager came into the bar and told the two men their table was ready. They climbed the stairs to the first floor and settled into two very comfortable chairs in a corner.

‘You know,’ said Pete, tucking into his sole with relish, ‘you ought to concentrate on writing novels. You never seem to be under as much strain when you're doing that.’

‘True, but novels don't pay as well as screen writing. I have a great objection to film companies’ buying good stories for peanuts, then employing someone at a very high fee to write a screen play.’

‘Maybe you're right, but the money you earned at novel writing didn't leave you exactly poverty stricken,’ said Pete, pouring out more wine.

‘That's true. Maybe after I've finished the television project, I'll get down to writing a novel.’

‘Any idea what you'll write about?’ {7}

‘I don't really know, but I've always wanted to write a book about the last few seconds of life. I've often thought that in those moments one might see something of the future,’ said Mike seriously.

‘You mean to say that when I snuff it, there will be a moment before death, when the whole future that I might have had will flash before me?’ asked Pete with solemn interest.

‘Something like that. With all the talk of E.S.P., and other forms of telepathic communications, I think it might sell.’

‘It's a bit gruesome, isn't it?’

‘Not really. Think of what one can say. I could even include my thoughts on the inevitable collapse of civilization as we know it today.’

‘That's sheer pessimism. Everyone knows the dangers of overpopulation. Surely something will be done about it?’ said Pete confidently.

‘Maybe, but I feel that it's been left too late. Scientists are not allowed to do much about it, and the politicians won't, for fear of being unpopular.’

They ate in silence for a few minutes.

‘There's only one snag to that bright idea of yours: each person's idea of his future might be different?’ said Pete, emptying the wine bottle.

‘Yes, that's true. Each one of us is conditioned to certain outside events, and finally we will be limited by these conditions. Look at the amount of conditioning the general public have had about the threat of a nuclear war. If this conditioning was released at death, most of them would probably only see their future in relation to a third world war.’

‘I think you're going to have one hell of a problem writing this little lot up,’ Pete said, smiling at Mike, who grinned back.

‘That's why I must get some massage, otherwise my typing shoulders won't be able to function properly.’

The meal over, Mike and Pete made their way out of the restaurant into the street. A clock above a shop showed nine forty-five. The two men started strolling leisurely back to Frith Street. The June evening was still hot, but not too heavy.

‘Are you going to sit in with us?’ asked Pete as they re-crossed Shaftesbury Avenue.

‘I shouldn't think so, but I'll come in for a while.’ {8}

The club was not full. Pete made his way backstage while Mike squeezed onto a small table with four other jazz enthusiasts. The five-piece band, with Pete playing drums, thundered away for over two hours before they took their first break. Mike came out of his semi-conscious state when Pete got hold of his arm and dragged him to the bar, for whisky.

‘Do you want to tinkle the keys?’ Pete asked, passing Mike a large full glass.

‘I'm glad these are on the house.’

‘That's not what I said, man.’

‘I know. No, I don't feel like it. I must say you've improved since Christmas.’

‘What? I was so high I don't remember Christmas.’

‘I know. You brought Christmas up all over Sue's new carpet and then fell in it.’

‘You didn't do a good job in cleaning up. I remember smelling myself at New Year.’ Pete started to laugh.

‘Cleaning you up. Easier said than done. Have you ever tried bathing two hundred and twenty odd pounds of giggling fun?’

‘No, but I'd sure like to try,’ said Pete, pushing an elbow into Mike's side.

‘Pete, before this conversation drops much lower, I think I'd better make my way home. How about dinner tomorrow night? I'll be here about seven.’

‘Sure, that'll be great. Don't forget your massage,’ said Pete, putting his arm round Mike's shoulders and giving them a squeeze.

‘I won't,’ Mike said, looking for somewhere to put his glass down.

‘You're not feeling sad now, are you?’ asked Pete quietly, as they moved into the fresher air of Frith Street.

‘I don't feel depressed, just tired.’

‘Sure, and you'll find Uncle Pete was right about that bitch.’

‘Come off it. She had her bad side, but she also had some warmth,’ Mike said defensively.

‘Of course, and from looking at you, you could do with some warmth to bring you in from the cold bad side.’

Mike laughed, gave Pete a feigned punch, bade him good night, and walked reflectively away.

The morning sun streamed in through the bedroom window. Mike opened a weary eye. From the height of the yellow {9} fireball in the sky he surmised that it must be around nine o'clock. A careful study of the sounds of the traffic activity in Albany Street convinced him. He opened both eyes, stretched, and reached out for his glasses. His guess at the time was only half an hour out. It was almost eight thirty.

Mike got up, turned the radio on and went into the kitchen. He put the kettle on, took a large old mug off a shelf, added two very large heaped teaspoons of coffee and retreated to the bathroom. He studied his beard in the mirror, then shaved. This chore finished, and no sound from the kettle, gave him time to put his contact lenses in. It took him a few minutes to clean them as they always seemed to be covered in muck, especially when he'd been in a smoky atmosphere. He put the clean right lens onto the tip of his index finger, opened the lids of his eye wide, and placed the lens on the iris. Vision came slowly into the eye as the lens settled. He repeated the operation with his left eye.

The kettle whistled and he poured the hot water into his coffee mug. There wasn't any milk. No woman, no milk. He shrugged his defiance and, equipped with his mug of black coffee, dressed. He slid into a pair of honey-coloured cords, and an almost matching roll neck sweater. A rummage round the bottom of the wardrobe produced his old desert boots, which he fought to get on. He closed the wardrobe doors. Sue hadn't been to collect her things or asked for them to be sent on. In a cowardly way he always hoped she'd come and collect her clothes while he was out.

Mike was now dressed, but felt aimlessly that he had nowhere to go. Be industrious, he thought to himself, looking at his desk. He didn't really want to get down to work, so he compromised. He would first go for a massage. He remembered Pete's enthusiasm and booked an appointment, with what sounded like a very sexy voice. He finished his coffee, picked up his old well worn suede jacket. A feeling of guilt swept over him, as he looked again at the notes for the television idea but before his conscience could get the better of him he'd left the flat and descended to the lobby.

‘Morning Sam,’ said Mike, as he sauntered through.

‘Good morning, Mr. Jerome. Lovely day outside,’ observed the commissionaire.

‘Lovely. I'll pick my mail up on my way back,’ Mike said, opening the outer doors.

‘Very good, Mr. Jerome,’ Sam called after him.

The morning air smelt great, as Mike worked his way to the outer circle of Regent's Park, instead of bus-ing it {10} down Albany Street. Rush hour was at its peak, and it took him a few minutes to cross the road. Every time he came back from abroad, he found himself looking left first instead of right. Making his way to the central path running through the park, he turned south and walked steadily along, relaxing in the fresh air. On a morning like this, he began to think of holidays in the sun. It was ages since he'd had a real break, in fact the last time must have been five years ago.

Mike crossed Euston Road to Regent Crescent. On seeing the B.B.C. building at the end of Portland Place, he made a mental note to pop in and find out whether there was any work he could do for them. He turned into New Cavendish Street, and made his way to Harley Street. The houses all had a neat, well-kept appearance. He walked to the end of the street, checked the time, as he didn't like the idea of waiting too long, then turned and, walking back, punched the appropriate door bell. When no one came he tried again. Still no results, so he pushed the bell good and hard, and when nothing happened, grew impatient and tried the door. It didn't open, so he gave a really hard push. At the same moment the door gave and he flew into a quietly lit passageway. Gathering himself together he realized that someone was standing there closing the door behind him.

‘Sorry about that,’ said Mike, trying to see clearly the person who opened the door.

‘That's quite all right, it was my fault, I was on the telephone,’ said an extremely attractive woman. ‘You must be Mr. Jerome.’

‘Right,’ said Mike, staring a little. Pete had been right.

‘This way please, I shall be ready for you in a moment,’ said the woman showing him into a small waiting-room.

Mike slowly paced round the room. On the wall were hung old sporting prints, and on a table in one corner was a collection of Country Life, Motor and Punch.

‘Mr. Jerome, I'm ready for you,’ said the woman, coming in through a communicating door dressed in a white coat. Mike smiled and followed her.

‘You can undress here,’ she said, indicating a small cubicle.

‘Tell me,’ asked Mike, undressing, ‘I didn't catch your name on the phone.’

There was a delightful laugh. ‘Colleen, Colleen Winston.’

‘Irish?’ asked Mike.

‘I don't think so. All I know is that my father was a great romantic.’ {11}

‘You know the friend who told me about you really underestimated your good looks,’ said Mike dreamily from the couch.

‘Really, and who was this friend of yours?’ asked Colleen gaily.

‘Pete Jones, plays drums in a jazz club in Soho. Do you like jazz?’ asked Mike feeling the vibrating machine rubbing hard into his knotted back muscles.

‘Yes, but I think Pete found me very naive,’ said Colleen.

‘I wouldn't say that.’

‘Wouldn't you,’ laughed Colleen. ‘What do you do for a living?’

‘Write.’

‘Anything in particular?’

‘No, not really. I flog certain hobby horses in everything I write but I work on anything,’ said Mike, beginning to relax under the treatment.

‘Why do you write?’

‘I suppose, I suppose I like to entertain people,’ Mike said thoughtfully, ‘or at least to take them out of themselves. And maybe make them think a bit.’

‘Have you ever thought of writing science fiction?’

‘Yes, but I'm not a scientist and an idea has to have a smack of authenticity about it to appeal to me. Given a scientific theme, I reckon I could construct a good plot.’

‘If you could talk to a scientist, would that help?’

‘Of course, but most scientists are far too busy to be bothered,’ laughed Mike.

‘Well, I have a client, a physicist at London University, who is always saying writers can't get the science right. Would you like me to give him a call and see if he is interested?’

‘Certainly.’

‘Any time suit you?’

‘Yes, my time's my own.’

‘Good, I'll give him a call. I'll be back in a moment.’

Nice woman, thought Mike as the rubbers massaged deeply into his back. He began to feel a little giddy, almost as if he'd been out in the sun for too long.

‘Did you get hold of your client?’ said Mike, raising himself on one arm, as the woman reappeared.

‘Yes, he said he'd be at the physics department, just behind the Royal College of Music, all morning on the sixth,’ she said shyly.

‘Day after tomorrow, that sounds fine. I'll be sure to go {12} along. Whom shall I ask for?’ said Mike, getting off the couch, and going into the cubicle.

‘Professor Smitt.’

‘Right. And thank you very much,’ said Mike, coming from behind the screen.

The sixth dawned another beautiful day, and as Mike walked down Albany Street looking for a taxi, he wondered whether Cornwall would be a nice place to continue his ideas for the television programme. Then there was always a possibility that this Professor chap might suggest something useful.

Mike took a taxi to the Royal College of Music. He walked round the block to the back of a complex of buildings and eventually spotted a sign saying, ‘Engineering Department.’

‘Excuse me,’ said Mike to the doorman, ‘is there a physics department here?’

‘No.’ The man said slowly, ‘no, not that I know of.’

‘Thank you,’ Mike said, turning to look elsewhere.

‘They might be able to help you in the Engineering Department,’ the doorman said calling after him, ‘along the corridor, first door on the right.’

‘Thank you,’ called Mike to the man.

He pushed the door to the lab open shivering for an instant in the sudden cool. The large laboratory was filled with the usual apparatus, electrical wiring, heating equipment and scientific hardware dotted around on various benches.

‘Can I help you?’ came a pleasant voice from the lab.

‘Yes,’ said Mike, walking in the direction of the sound, ‘I'm looking for Professor Smitt.’

‘Hang on, he was around here a few minutes ago,’ said the fresh-faced young man.

‘Thank you.’

‘Mr. Jerome?’ said a tall, thin man coming from the direction of an office.

‘Yes.’

‘Smitt, Professor Smitt,’ said the man, smiling and holding out his hand.

‘I thought I might have got the wrong building,’ said Mike, shaking hands.

‘No, no, I was expecting you. Colleen Winston tells me you're an author.’

‘That's right, Professor.’

‘You make a living at it?’ asked the man, smiling.

‘Yes. The first years can be rough though.’ {13}

‘I'm sure that's true, as it must be in many creative fields,’ said the Professor with a fatherly smile. ‘Well, not to waste any time,’ he continued briskly, ‘I think it would be simpler if I told you the idea I had in mind, then you can tell me what you think. Let's go into my office.’ He turned to look intently at his visitor. ‘You know Einstein had a theory called “The Time Dilation”, or just simply “Time Dilation”. Now it occurred to me that one might use this idea in a story.’

‘Rather like H. G. Wells, you mean?’

‘Well, the device would be different from Wells's Time Machine. You see, if we were to travel away from this planet at the speed of light, we would age very little in comparison with the people left here on earth.’

‘I see, so if I were shot away in my high-speed rocket and returned in, say, five years Earth time, people here would be five years older, but I might be only a few minutes older?’

‘Yes, but please remember, there is one very important point in telling time stories, and that is it is not possible to go backwards in time.’

‘So I've heard, but never understood why,’ said Mike.

‘For the moment, let us say that, as far as physics is concerned, one can only go forward. I think to offer you a scientific explanation at this stage would perhaps be too confusing,’ smiled the Professor.

‘If one packs humans into a rocket that travels at the speed of light, even enthusiastic science fiction readers might be a bit sceptical,’ Mike objected.

‘Yes, I agree.’ The Professor nodded briskly. ‘I would say that one could use some source of light, perhaps a laser beam. Reduce the human structure into a form that can be transmitted as electrical pulses, shoot this information down our light beam, and at a convenient point reflect it back.’

‘Very good, but how far can you reduce the human form into electrical information and how would you convert it back again?’ asked Mike, liking the idea.

‘I think you would have to use an explosive breakdown of the human form, involving a highly organized source of energy. To reproduce the information you could use a hologram picture of the total information. So if we used you, before we could proceed we would need such a three-dimensional picture. When the information came back, it would be passed back through the hologram picture and there you'd be. Here, I've jotted down some notes for you.’

‘Thank you, Professor. It sounds most intriguing and certainly I'll be glad of the notes. Probably the best thing for me {14} to do is to go away and write up a format and then let you read it,’ said Mike, holding out his hand.

‘I shall look forward to reading it,’ said the Professor.

‘If this goes as a television project there's going to be money involved. How would you see your part in this?’ asked Mike politely.

‘What do you suggest?’ smiled the thin man.

‘Well, if we get paid for the format, how about a fifty-fifty split?’

‘I think that sounds very fair,’ said the Professor.

‘Oh, by the way, do you think it is possible in the last moments before death, to see a certain amount of the future?’

‘It's a thought, but without having the experience I couldn't really say,’ said the man with a jovial twinkle in his eyes.

‘Thanks,’ said Mike, jauntily walking away. The time idea was good. He started to hum as he left the building.

‘It's dogged as does it. It ain't thinking about it.’

Trollope

STANDING on the pavement, he wondered what to do. The urge to go back to the flat and write was strong, but he felt reluctant to leave the clear sunny morning. He knew he would have to wind himself up. He didn't know why, but he worked better under tension. When he finished whatever he was writing, he was like a wet cloth.

Defiantly spinning on his heels a couple of times, he set off in the direction of Hyde Park. He aimed a light kick at a piece of paper lying conspicuously on the edge of the pavement. It rose about a foot in the air before being sucked away into the middle of the road by a passing car. That's life, thought Mike as he stopped to cross Kensington Gore to Alexandra Gate. The lunchtime traffic was dense. Cars, vans and lorries roared by giving no time to cross, unless one were an Olympic hundred-metre gold medallist. Mike held up his hand to the oncoming traffic and stepped out into the road. Cars manoeuvred to avoid him, and eventually he reached the island in the middle. He looked up at the traffic light standard, but the signals weren't visible. Mike shook his head at a {15} motorist trying to inch into the road from Alexandra Gate. Typical British efficiency, he thought to himself as he made a dash for safety.

The Metropolitan Police were exercising their beautifully groomed horses, completely unaware of the chaos building up outside the Albert Hall. Mike waited for the horses to trot by and crossed towards the Serpentine. Small boys knelt by the water playing at being admirals and ships’ captains, while their coloured blocks of wood plied backwards and forwards over a few feet of water. The line of prams with their custodians in neat pressed uniforms reminded Mike of a picture of a royal gathering in Elizabeth the First's time, watching some gallant sailor going off to sea. He made his way round to the east end of the lake, to a small coffee shop. A duck looked at him from the water and laughed in a cynical fashion. The smell of newly-mown grass was strong, and Mike could almost hear the sounds of a Sunday afternoon cricket match on the village green.

‘Yes?’ said the mini-skirted waitress, showing off her hips by shaking them.

‘Coffee, please,’ said Mike, sitting down at the small metal table.

‘Anything else?’ inquired the girl. Mike shook his head, and the girl turned, revealing a very compact behind.

A motley selection of humans sat stuffing their stolid faces with cakes and inedible-looking sandwiches. No wonder the British economy was in such a pathetic way. Mike couldn't quite see these people around him as the driving force behind the swinging, advancing, new economic growth that the Government had been urging.

‘That'll be one and nine,’ said the waitress. Mike felt in his pocket and produced a handful of pennies. He laboriously counted out the money, but was four-pence short. In his wallet he found three ten-pound notes. The girl grudgingly took one.

‘Your change,’ she said curtly, bored with this inattentive young man.

Mike felt elated as he began to ponder on the morning's meeting. A boat with a young couple in it nosed its way gently along without the assistance of oars.

The idea that Professor Smitt had mentioned to him was developing. Although much had been written on time travel, he felt that the new idea had the makings of a very good story. His central character would be a musician, perhaps a {16} top-flight concert pianist who knows that his illness cannot be cured for some time to come. He is involved with an eccentric physicist, who suggests that he should be thrown forward in time, say ten years. The pianist is both amused and angry at the ridiculous suggestion, but after consideration he goes back to see the professor. The man has vanished. He searches round the laboratory, and without warning is swept up into a time change. The mechanics of the time change could be left to Professor Smitt, Mike thought, as he finished his coffee.

He left the coffee shop, and strolled towards Marble Arch. The urge to work was now very strong. Mike decided to go home and start writing. As he walked along the green turf, the story began to take shape. Once the pianist was in the time machine each episode could deal with another period in time. One reason would be that the pianist was summoned from his own time to a future where music has almost been lost, and musicians were needed to fill the gaps. The stories should be almost pure adventure but with a strong social background. In fact, if there were going to be thirty-two or -three episodes, then the overall social picture could be the slow breakdown of civilization as one knew it today. Mike's mind was now really racing. Once he'd sketched the outline, he could see the television people to find out their reaction. If he worked into the night he felt he could get the outline done, and tomorrow go to the TV company.

Reaching Park Lane, he was just about to hail a cab when he changed his mind and descended into the subway leading to the Marble Arch tube station. He found a telephone booth and dialled Pete's flat. The phone was eventually picked up and the line started to blip. Mike forced in a sixpence and waited for the machine to digest it.

‘Hello, Pete?’

‘It's not dinner time yet, is it?’ came a very sleepy voice.

‘No. Listen carefully. I'm going back to the flat to do some work. I want to get a story outline finished tonight, so I think we'll have to scrub dinner unless you want to drop round for a bite later on,’ Mike said in a rush.

‘Going home to write. Can't afford to take me to dinner, so collect food and come round when I'm ready,’ came Pete's yawning reply.

‘That's it. What time?’

‘Seven,’ Pete said and the phone went dead. Mike replaced his receiver, and smiled.

He bought a ticket and made his way via Bond Street and Oxford Circus to Regent's Park. Here he came back into the {17} sunlight, and walked quickly up through the gardens. He passed through a small alleyway to the front of the block of flats where he lived. He was about to go in, and stopped. He wasn't quite sure why he'd stopped and then remembered that he still hadn't any milk. He crossed the road, heading towards a small grocery shop where he bought milk and a large jar of coffee. He didn't really like instant coffee, but when he was working it was simpler to make than proper coffee.

He hurriedly left the shop, and reached Albany Street. Clutching his parcels, he stopped, looked left, and stepped off the pavement. His momentum carried him several yards into the road before he looked right. It was too late. The taxi was on him. The driver must have applied his brakes hard—blue smoke rose from the taxi's front tyres. Mike stood transfixed in horror as the vehicle rammed him. He felt the hard metal cut into his legs, before he was thrown up in the air and tossed over the bonnet of the taxi. Mike felt himself hit the tarmac, with a sickening thud. He heard voices and the sound of running footsteps, but consciousness was slipping away. The world around him began to blur grey and then dark grey. Suddenly he saw a small fireball somewhere above him. From this ball of light came small darts which, curving rather than moving in a straight line, seemed to go straight into his head. Everything exploded into tiny fragments of light and he passed into the world of unconsciousness.

Mike's head felt as though he'd been run down by a jet plane. Even with his eyes closed he could still see the little darts of light. Suddenly, whatever he was lying on moved, and he opened his eyes. He found himself being lifted out of an ambulance.

‘Glad to see you're still with us,’ said a cheerful voice.

‘So am I,’ said Mike coughing violently.

He was carried in through large swing doors, down a small corridor to the outpatients. Mike coughed again as he smelled the heavy odour of disinfectant. The stretcher was carried into a cubicle, and left. Mike ached all over but there was no pain except in his chest. He moved his hands over the parts of his body he could reach, and to his joy found no broken bones.

‘What have we here?’ said a peppery-looking man.

‘Carbon monoxide poisoning,’ said a younger man. The peppery-looking man started to give Mike a simple examination. {18}

‘Carbon monoxide poisoning?’ said Mike, dumbfounded.

‘You'll be all right. Just a simple injection, and you'll be able to go home,’ said the older man, preparing it. The younger man rolled up Mike's sleeve, and he was given the injection.

‘There. You'll be as right as rain,’ said the older man, throwing the syringe away, and leaving the room.

‘Carbon monoxide poisoning,’ Mike repeated.

‘Yes,’ laughed the young intern, ‘what do you think you've got?’

‘I thought I'd been knocked down by a taxi.’

‘Pity you hadn't, it would have given us something interesting to work on. I think you'd have a job nowadays to get run down,’ said the doctor picking up a sheet of paper. ‘Now, can I have your insurance number, health insurance number.’

‘I'm sorry I don't know it,’ Mike said, wondering what the man was talking about.

‘You must have an insurance number.’

‘If I do, I'm sorry I can't remember it.’

‘Then I'm afraid you'll have to pay for the injection.’

‘How much?’

‘Oh. Six pounds,’ said the intern casually.

‘Where have you been?’ said the intern, looking at the pound notes Mike gave him.

‘Nowhere,’ Mike said, beginning to get fed up. ‘Tell me, what is this business about insurance numbers?’

‘Didn't you get all the bumf, when they changed over from the old National Health Scheme?’

‘No, I'm afraid I didn't,’ said Mike, in great confusion.

‘Well, it's a useful policy to have. You can get one from any insurance company. You know, just like a car insurance policy. You pay a fixed premium to begin with. Then if you have no claims in the year they reduce your premium. You ought to see about it, medicine can cost an awful lot nowadays.’

‘Thanks for the information,’ said Mike, getting up off the stretcher. ‘What hospital am I in?’

‘University College Hospital,’ replied the intern. ‘Do you live far away?’

‘No,’ said Mike. ‘Tell me, why does an injection cost so much?’

‘It's not the injection that's expensive, it's the doctors’ time and things like the ambulance. Drugs only cost a few pence, {19} except for the anti-tissue rejection ones,’ said the intern, opening the door.

‘What is a Terminal Ward?’ asked Mike pointing at a sign above a door.

‘We send cases there that might not live more than twelve hours after they've been admitted. If they live for longer, but turn into cabbages, then they are allowed to die. Do you feel all right?’ said the doctor, somewhat concerned by Mike's questions.

‘Fine, just a little confused,’ said Mike trying to force a smile.

Mike left the intern looking after him strangely and walked to the entrance to the hospital. Something must be very odd, Mike thought, as he found himself in Tottenham Court Road. He turned and looked up at the ultra modern building behind him. Tottenham Court Road seemed to be full of traffic. Mike looked at his watch. It showed twelve forty. He held it to his ear, but it had stopped. He crossed the road, and walked to the corner of Euston Road. All the traffic was stationary, and to Mike it looked like a rush hour stoppage on a Los Angeles freeway.

A man came running through the cars towards Mike.

‘Excuse me,’ said Mike to the man as he reached the pavement.

‘Yes?’ said the man nervously.

‘Could you tell me the time, please?’

‘Two twenty-four.’

‘Thank you, isn't this traffic terrible?’ Mike said, adjusting his watch. The man looked hard at Mike, and then muttered, ‘I suppose so,’ and hurried off towards a large building. The traffic in front hadn't moved. A frightening feeling of not knowing where he was slowly seeped through Mike. Everything was different, all the old buildings on the south side of Euston Road had gone. In their place now rose a giant structural complex. Mike hurried along back to the familiarity of his flat. He felt the bang from the taxi had done something to his sense of reality. If this were so, he puzzled, then why had the doctor given him a shot for carbon monoxide poisoning, and why were none of his limbs broken? The fear of this Alice in Wonderland feeling grew as Mike neared his flat, and he broke out in a cold sweat.

His apartment block looked the same as he pushed his way through the main entrance and hurried to his own front door. He inserted his key and tried to turn it. Nothing happened, it wouldn't turn. Panic was now rising quickly. Mike {20} tried to force the key to turn. Finally he pulled the key out of the lock and pressed the door bell.

‘Yes,’ said a dark haired woman. Mike looked at her in blank astonishment and pushed into his flat.

‘Hey, what do you think you're doing,’ cried the woman angrily.

‘I live here,’ said Mike curtly, walking into the living-room. ‘What the hell's going on?’ he yelled, looking at the room. All his furniture had gone, replaced with alien stuff.

‘How dare you,’ shouted the woman. ‘This is my home, and has been for a long time.’

‘Don't be bloody stupid. This was my flat when I left here this morning, how could you have lived here for a long time?’ Mike shouted back.

‘Young man,’ said the woman fighting for calmness in her voice, ‘I have lived here for a little over nine years, and, if you won't leave, then I'll have to call the police.’ She moved towards the phone.

‘You've lived here . . .’ Mike felt his legs go weak, and he almost fell over.

‘Are you all right? You've gone a very strange colour,’ said the woman.

‘May I sit down for a moment?’

‘Well. As long as you go when you feel better.’

‘Yes,’ said Mike, sitting down thankfully.

‘Tell me,’ he said at length, clearing his throat, ‘have you got a newspaper?’

The woman looked at him, and then handed a paper to Mike who took hold of it eagerly, and searched for the front page, ‘june 6th, 1979’ read the date. It was unbelievable.

‘This must be someone's idea of a very bad joke,’ he said weakly.

‘I don't understand?’

‘It can't be 1979,’ said Mike, with a nervous laugh.

‘Well, it is, and if you don't leave, I shall call the police.’

‘I'm sorry, Mrs. . . .?’ said Mike not knowing quite what to say.

‘Mrs. Peters; now will you leave?’

‘Yes, of course,’ he said, standing up. ‘Tell me, who did you buy the lease of the flat from?’

‘Please, whoever you are, will you kindly leave,’ said the woman.

‘Was it through a black jazz musician called Pete Jones?’ said Mike, reaching the door.

The woman was so taken aback that she said, ‘Yes.’ {21}

‘Thank you, Mrs. Peters, I'm sorry to have been such a nuisance.’

The door to the flat crashed shut behind him. ‘Bloody bitch,’ he said to himself as he descended in the lift. He had been positive that he'd been hit by a cab on June 6th, 1969, at around lunchtime, but now he wasn't sure. Perhaps he'd just had a mental black out, and Pete was playing a joke. The trouble was that Pete didn't have that type of macabre sense of humour. Mike walked through the lobby to the main door.

‘Mr. Jerome,’ came a cry of horror behind him.

‘Sam,’ said Mike in great relief.

‘That's right, Mr. Jerome, we all thought you was dead,’ said the old man, staring as if he were seeing a ghost.

Mike couldn't find anything to say, until a thought struck him. ‘Sam, what happened after I was knocked down by the taxi outside here?’

‘They took you away in an ambulance.’

‘Who did?’

‘The ambulance men, Mr. Jerome,’ said Sam, beginning to look frightened by the inquisition.

‘O.K., don't look so worried Sam,’ said Mike. Out in the street he stopped to collect himself as best he could. It was all a bad nightmare. Find Pete, thought Mike. Pete would be solid reality, and once he was found, the rest of the joke might start to fit into place.

If it were truly 1979, that would explain the traffic, that seemed to be stopped in a permanently snarled up rush hour, thought Mike as he went along. It would be a logical progression from the rush hour jams of the past. At Portland Street Station he barged his way through the crowds. He searched the ticket hall for a phone but there was no sign of one.

‘Excuse me,’ said Mike to the man behind the grill of the ticket office, ‘where do I make a phone call from?’

‘Post Office.’

‘Fine. Where would I find a post office?’ said Mike, feeling the eyes of curiosity staring into his back.

‘Down by Warren Street Station,’ said the man in the monkey's cage. Mike struggled back into the street. The sky scrapers that loomed up round him made the old G.P.O. Tower look rather like a garden gnome. A large sign appeared on his right indicating that there was a Post Office in the next building. The door slid open and closed as he passed through. A flashing sign showed the way, a long moving escalator. {22} Mike was carried down into a fluorescently lit sub-basement. In front of him as he stepped off the stairs was a large gallery, containing the Post Office, an impressive array of different banks, and what looked like a large jewellery shop.

‘I'd like to make a phone call,’ said Mike to a woman behind a counter marked telephones.

‘Number?’ said the woman as she finished with another caller.

‘727 9209,’ he said, risking that Pete wouldn't have got round to changing his number.

‘Booth number 17,’ said the woman pointing. Mike found the right box and picked up the phone which just appeared to be hanging from the wall.

‘Please replace your receiver until you are called,’ barked an officious voice. Mike looked at the wall and then at the phone. Where the hell was he meant to replace the bloody thing? A small hook in the wall eventually caught his eye, and he attached the phone onto this. If this was really 1979 then he didn't think much of it. The whole atmosphere was rather like walking through a thick, damp fog. Mike shivered. Bip, Bip, went the phone, so he picked the instrument up from its hook.

‘Your number is ringing,’ said the voice. Mike heard the Bip, Bip, Bip and then silence for a moment before the signal repeated itself.

‘Park, no I mean 727 9209,’ suddenly said a very familiar voice. Sudden tears welled up in his eyes and his throat felt tight and dry.

‘Pete, are you thoroughly awake?’ Mike said, clearing his throat with some difficulty.

‘Yes, of course I am, who is it?’ came a rather testy reply.

‘Pete, this is Mike Jerome,’ Mike said, trying to hold back the tears.

‘Mike?’ Then there was silence.

‘Pete, are you all right?’ asked Mike urgently.

‘Man, if it's really you, then I'm O.K.,’ came a very unsteady voice down the phone. ‘Where are you?’

‘I'm at Warren Street Station, or thereabouts. Where are you?’

‘Same old place. Look, it isn't worth me getting out the limousine, as the traffic is really f . . . awful. Can you make your way over, I think it would be easier.’

‘Of course. Look, if the traffic is that bad, then I might have to walk, so expect me in say an hour or so,’ said Mike beginning to feel contact with the world at last. {23}

‘About an hour, great, Mike, that's just great. Till then,’ said Pete.

‘Till then,’ Mike said excitedly, and replaced the phone.

Mike was just about to leave the Post Office when he remembered that he would have to pay for the call. He went back to the counter, and waited his turn.

‘That's ten pence.’

Mike felt in his pocket and took out all his loose change. He counted out ten pence and pushed the money over the counter. He didn't wait to hear what the woman called after him.

The streets were still crowded and Mike's patience was beginning to wear thin. He looked round until he saw an empty cab but the driver was nowhere to be seen. He would have been happy to pay well over the top, not to have to walk to Pete's. He went to the tube station just in case, but it looked hopeless. The vast numbers of people walking were not shoppers, as he'd originally thought, but workers. He wondered whether there was a special reason or if the chaos was normal. As Mike walked on into Marylebone Road, all the old buildings he remembered were gone. In their place towered huge sky scrapers. He stopped from time to time to see what they were used for. To him they looked like office blocks, but from studying the long lists of names inside the buildings it became apparent that there was a large residential population. This struck him as very logical. If one couldn't commute to work, then one would have to live near one's work. How pleasant, thought Mike, he could find himself a superb new flat. A penthouse, perhaps. Resilience returned.

|

‘Love Love is money, Cheri.’ |

Jacques Prevert

MIKE turned buoyantly into Craven Hill and walked across the road to Pete's flat. There, standing on the front steps of the house, was a dark form.

‘Man, I couldn't believe it, I couldn't believe it,’ said Pete, {24} leaping down the steps to greet Mike. The two hugged each other in a long embrace.

‘How are you?’ said Mike, seeing the tears in Pete's eyes.

‘Great. A little over-weight,’ said Pete, patting his trim-looking stomach. ‘Come on, come in, you bloody bastard.’

Mike followed Pete up the stairs and into his flat. Inside Mike took hold of Pete and gave him another bear hug.

‘You know, you really had me worried,’ said Pete, going over to a low table and pouring out two of the usual drinks.

‘You're not the only one,’ said Mike, helping himself to a splash of soda. ‘Did you have a bad time?’

‘Man, did I have a time. I was accused of hiding you, killing you, encouraging you to run away, and after all this I had the damned police on my back for months,’ Pete said with a big grin. ‘You know, the worst person was that damned bitch, Sue.’

‘What the devil was she doing?’

‘She was the one who put the police onto me. She never really liked me, and since I'm black everybody had it in for me,’ said Pete, taking a seat. At this moment a rather embarrassed-looking girl came out of the kitchen wearing nothing but her pants.

‘Honey, why haven't you got dressed?’ said Pete.

‘You two didn't give me very much time, did you,’ came the reply.

‘This is my oldest and best friend, Mike,’ said Pete with pride.

‘Hello,’ said Mike.

‘I've heard an awful lot about you, Mr. Jerome,’ said the girl with a twinkle.

‘I'm sure you have,’ said Mike, looking at Pete.

‘Honey, the man's name is Mike,’ said Pete. ‘Mike, that's Guy,’ he said, as the girl left the room to get dressed. ‘Another drink?’

‘Tell you one thing I'd like to do, and that is to eat early,’ Mike said, getting up and starting to prowl around the room.

‘Sure, we can nip round the corner to the Indian place,’ said Pete, handing Mike his glass.

‘Tell me, Pete, what's the date today?’

‘Sixth of June, I think.’

‘So that makes it ten years to the day that I vanished.’

‘Right,’ said Pete, not pushing the matter, for which Mike was grateful. Pete probably knew more about his moods, and {25} the way Mike felt, than anyone alive. There were many times in the past when he'd had to come, cap in hand, to Pete for help. He suddenly stopped pacing when he saw his old desk.

‘It's mine, isn't it?’

‘Sure, it's yours. Haven't opened it since I got it. By the way, I've also got your old filing cabinet, but that's in store at the moment,’ said Pete shyly.

‘How did you get hold of it?’ asked Mike.

‘Well, Sue sold off all your stuff at an auction. Since she wouldn't let me buy it before, I went along and bought your desk, filing cabinet and all your papers,’ Pete said, turning the desk key in the lock.

Mike pulled open one of the drawers and revealed a mass of untidy papers. He put his arm over Pete's shoulder as he turned over a page or two of a manuscript. ‘God, look at this. It was an idea for that TV series I was meant to do.’

‘Yes, I had a few problems persuading the TV company not to sue you for breach of contract,’ said Pete.

‘Thanks,’ Mike said, pushing the papers back into the drawer and closing it. The old upright piano caught his eye, and he went over to it and started to rattle off a twelve-bar boogie blues.

‘You play very well,’ said Guy, coming into the room. ‘Where did you learn?’

‘From him,’ said Mike jerking a thumb at Pete.

‘Careful, Mike. Guy's looking for a good accompanist,’ Pete said.

‘Singer?’ said Mike, playing a jazzed-up version of ‘God Save the Queen’.

‘Right, you could earn some good money . . .’ Guy started to say.

‘I might hold you to that,’ said Mike interrupting.

‘Come on, you two. We've got some eating to catch up on,’ Pete said, picking up his coat.

It was almost four in the morning when Mike got into bed on the converted couch in the living-room. He had been pleased to find that food hadn't really changed, or at least not Indian delicacies. After their meal Guy had gone off to do her singing spot, at some new jazz club in the West End. Only then did Pete settle back to hear Mike's story. He listened to the whole saga without comment, merely asking Mike if he'd gone back to find Smitt. When he learned that he hadn't, he was relieved and advised Mike not to search him out. A heated argument ensued. Mike wanted to find out what had happened to him and was reluctant to remain in {26} ignorance. Pete, on the other hand, counselled him to leave well alone.

Then it was Pete's turn to fill in the missing ten years of news as far as he could. Pete cared for very little of what went on in the world, except the world of music, but even Pete was now aware that the politicians hadn't been able to effectively control the population growth and were blaming the explosion on the scientists, who, in their turn, were having to find ways of producing food stuffs in even greater quantities.

Mike slept well, and was feeling very cheerful when Guy brought him a cup of tea.

‘What do you want for breakfast?’ said Guy, still in her cabaret outfit.

‘Have you only just got in?’ asked Mike, raising himself on one arm to get at his tea.

‘Yes, I do two spots, one at eleven, and the other about two in the morning. Unfortunately the club doesn't close until the last drunk has crawled out,’ she said with a smile.

‘Well, if you're going to cook Pete his usual hearty breakfast, I'll have the same.’

‘Pete doesn't eat too much now, it's his heart.’

‘His what?’ Mike said, not believing what he'd heard.

‘His heart, it gives him trouble from time to time, so he has to watch his weight,’ she said, almost in a whisper.

‘Oh, well, anything will do then,’ said Mike, very disturbed about Pete.

‘Eggs, bacon and coffee, O.K.?’ said Guy, moving towards the kitchen.

‘Sounds like a feast. I'll have a few tomatoes if you've got them.’ Mike grinned to cover his worries about Pete. He waited until she'd gone, then he extricated his naked body from the pile of blankets, and went into the bathroom. God, he thought, as he found Pete's shaving equipment; the old cut throat looked really lethal. He studied his chin, there was no getting away from it, he'd have to shave. After finishing his death defying act, he washed his face. Drying it, he looked in the mirror. There were no contact lenses in his eyes.

Yet he could see. Mike shivered violently, and searched his eyes with the tip of his finger. The lack of his contact lenses brought back the whole insecurity of the previous day. What had happened in the last ten years? Did he, Mike Jerome, really exist, or was he dead? He pinched himself and the flesh seemed real enough. Slowly he finished dressing and returned to the living-room, where his breakfast sat steaming on the table. {27}

‘What's the matter?’ asked Guy, sitting down.

‘Nothing really. I'm just a little upset about Pete's health,’ Mike lied.

‘You mustn't worry, the modern drugs are simply wonderful, and if the worst came to the worst, he could always have a transplant,’ said Guy, very calmly.

Mike looked up from an egg as Pete appeared in a gloriously multicoloured dressing-gown. Mike blinked at this apparition. He obviously mustn't keep Pete up late in future. It was frightening. Pete really looked his age. Mike realized suddenly Pete must be ten years older than he was.

‘What do you plan to do this morning?’ he said, lowering himself into an easy chair.

‘Well, I suppose I ought to go to the bank, and see how much money I have. Then look for somewhere to live,’ Mike said thoughtfully.

‘Don't rush into finding somewhere to live. That reminds me, when you vanished I took most of your unpublished material to an agent, fellow named Gilbert. We should go to see him before we go to the bank. You might have earned yourself a lot of dough.’

‘What would this fellow Gilbert do with any money my work makes?’

‘I told him to pay it into your bank in Piccadilly. I couldn't think of anything else to do, and I knew that all your royalties were paid in there.’

‘You might be right. What shall we do if I've made a bomb?’ said Mike.

‘Buy a place in the country, away from the mess in this city. You can go on writing while I do some composing,’ said Pete, with a glint in his eye.

‘Good idea.’ It seemed strange to Mike that Pete had just let any money accruing from his work go into the bank. It sounded as though Pete always thought he would come back. He was aroused from his reverie.

‘Ready when you are,’ said Pete, finishing his coffee. Mike rose with alacrity and put his jacket on. He knew from experience that once Pete was ready, so were you. They went down to the rear entrance of the house, where Pete kept a murderous-looking motor bike. Mike immediately thought of the terminal ward in the hospital. The bike roared into life, Pete banged out the clutch, and Mike quickly grabbed the waist in front of him, otherwise he'd have been sitting on the floor. They sped down the street, again blocked by traffic. Pete stopped at the junction of Bayswater Road. {28}

‘Why don't these people stay at home if they're going to be stuck in traffic all day?’ Mike said to the back of Pete's neck.

‘They eventually get there, but it's a slow process,’ Pete said, letting out the clutch again. Mike hung on, wondering how much work these people did, or whether they got paid for the time spent in their cars. Pete's interpretation of the Highway Code would have interested a very capable lawyer. Where the road was completely blocked, they would weave across the pavement. If the pavements were full they'd somehow manage to avoid disaster by going in and out of the front doorways of houses and sky scrapers. The snarl of the bike's exhaust seemed to have very little effect on the pedestrians, and Mike had his eyes partially closed so that he couldn't be a witness to an accident.

When the bike stopped Mike opened his eyes. They were almost up against a large plate glass window.

‘Are we here?’ asked Mike, getting off. Pete nodded, dismounted and leant the bike on its stand.

‘Over there,’ said Pete, pointing at a building across the road. The two men made their way through the traffic and in through the main doors of the building.

‘Good morning,’ said the receptionist as they approached.

‘Hi, we'd like to see Mr. Gilbert of Gilbert Associates,’ said Pete firmly.

The girl smiled at Pete while she pressed the buttons on her intercom. ‘What name?’

‘Jones.’

‘Mr. Gilbert, there's a Mr. Jones and friend to see you.’

‘I'm sorry, if they haven't an appointment, I can't see them,’ came a voice from the intercom.

‘Mr. Gilbert,’ said Pete, ‘all we want to know is whether you've made any money for Mr. Jerome.’

‘Mr. Jerome, Jerome,’ said the voice, thoughtfully. ‘You mean the man who vanished?’

‘Right.’

‘Mr. Jones, I'm afraid I haven't the information on hand, so could you come back later today?’

‘I would personally, but my friend here, Mr. Jerome, I think is a little anxious to know what's been happening to his royalties,’ Pete said casually.

‘Hmm, you'd better come up,’ said the voice.

The two men took the lift to the first floor and strode down a corridor until they stood outside a door with Gilbert's name on it. {29}

‘Come in,’ came the reply to Pete's knock on the door. Gilbert got up from his desk and came over to greet them.

‘Well, Mr. Jerome, this is a pleasant surprise. I had understood from Mr. Jones here that you were probably dead.’

Tell me, Mr. Gilbert, what would you do with my money if I were dead?’

The man looked at Jerome in amazement, and then laughed. ‘Nice way of putting it, very nice,’ Gilbert said, sitting down. ‘After Mr. Jones brought your properties to me, I had to sell them. I did this and we waited for the seven years to expire before you were officially dead. The last year or so was spent searching for some relative to inherit.’

‘Did you find anyone?’ asked Mike, not liking the man.

‘Oh yes, we eventually found someone,’ smiled the fat, little man.

‘Who?’ asked Mike.

‘Mr. Jerome, there is no reason why I should tell you who got the money. If you are really the right Mr. Jerome, then you'll have to prove it to the courts, before you get your money back.’

‘What do you mean the right Mr. Jerome? Of course I'm the right bloody Mr. Jerome,’ said Mike angrily.

Then you should have no difficulty in proving it, should you,’ said Gilbert smoothly.

‘Who did you give my money to?’ demanded Mike.

‘Mr. Jones, I would suggest you get your friend out of here.’

‘How much did she get?’ Mike asked menacingly.

‘She?’ said Gilbert, a little taken aback, ‘I didn't say it was a she.’

‘No, but I know that it was a she. How much?’ said Mike, grabbing hold of the man.

‘Not much,’ choked Gilbert.

‘How much?’ said Mike applying pressure to the man's throat.

‘A little over twenty thousand pounds,’ coughed Gilbert.

‘Bastard,’ Mike said, not letting him go.

‘Thump him, don't kill him,’ Pete said taking hold of Mike's arm.

‘Why bother?’ Mike said, dropping the now gasping, sweating Gilbert. ‘I'll tell you one thing, Gilbert, you'd better warn your friends that I have every intention of getting my money back. If I can't do it through the official channels, then I'll do it on my own.’

Pete grabbed hold of Mike and pushed him out of the {30} room. ‘Man, you can't go around threatening people without proof.’

‘Pete, you know as well as I do that Sue got the money, and I'll lay any bet that that little punk took a fat cut,’ said Mike vehemently.

‘So, what are you going to do?’ Pete asked, as they reached the street.

‘Wait. If I'm right, they'll be in touch with each other immediately. I have a feeling that they'll make the next move.’

‘What can they do?’ said Pete thoughtfully.

‘Their best bet would be to call the police in and try to disprove my story.’

‘Which they will do, without any difficulty,’ Pete said.

‘Right, but by tonight I'll know where that bloody bitch lives.’

‘I don't like it. Look, Mike, why don't you just go to ground?’ said Pete anxiously.

‘As soon as I know they realize I'm around,’ Mike said, with a curious laugh. ‘Come on, since I don't seem to have any credit with Mr. Gilbert, we'd better see how the old bank balance is faring.’

‘And what are we going to do with all this money in the bank?’ said Pete, recovering from the interview with Gilbert.

‘Celebrate, go on an absolute blinder,’ said Mike. Pete's face showed great delight and fear.

The two men danced happily across the road to the bike.

‘To the bank, sir,’ said Pete, with a little bow, as Mike got onto the machine.

‘Quite right, to the bank,’ said Mike grabbing hold of Pete's waist in good time. Pete pressed the starter and the bike's engine roared into life.

‘Let's go,’ yelled Mike, above the noise of the engine. The bike left the pavement in a cloud of rubber smoke.

They wove their way down Regent Street, and into Piccadilly Circus. The circus was now a vast complex of modern buildings standing well back from the road. Eros was still the centre of the circle, but instead of concrete there was almost a field of grass surrounding it. Mike looked round for his bank, but it was nowhere in sight. Pete parked the bike and removed its keys.

‘Won't you get done for parking?’ asked Mike, as he followed the burly figure in front of him.

‘Nope, the traffic situation is so bad the authorities don't really care too much,’ Pete said, with a wave of his hand. He {31} led the way down a subway, and along a passage until they came to a large underground shopping centre. They walked down a Burlington-type arcade until they were standing outside Mike's bank. It didn't look big from the outside, but once inside the place was vast. The two men walked across the marble floor to the nearest teller's window.

‘Good morning, 1 would like to see my statement,’ said Mike cheerily.

‘Over there,’ said the teller, hardly looking up.

Pete pointed the room out and then left Mike to look at the ticker tape machine. Mike typed out his request to see his statement, read it and destroyed the information in a waste paper shredder. He returned to the teller for a new cheque book and withdrew two hundred pounds from his account. With his money safely in his wallet, Mike pulled Pete away from a second ticker tape machine which was churning out the stock market results. From the bank they made their way back into the carbon monoxide fumes.

‘Where to now?’ asked Pete, as they reached the bike.

‘Let's pick up a drink then I'll find out where Sue lives.’

‘Man, I agree with the drink part, but leave well alone. Surely you've got enough cash to be going on with,’ said Pete, in distress.

‘Maybe I should leave it alone, but it's the principle. Why should they get away with stealing?’

‘I agree, but the story you told me won't get you anywhere. You'll be shut up in a nut house.’

‘All right. I'll tell you what I'll do. I'll find out where she lives, and then I'll leave everything until she and Gilbert make a move,’ said Mike.

‘I still don't like the idea,’ said Pete, getting on the bike. Mike got on behind and they shot off back to Bayswater. They left the evil machine outside the house, and walked round the corner to Pete's local.

‘You know, I think I'll go and live abroad,’ Mike said as they walked. ‘But the question is—where?’

‘The old problem,’ laughed Pete as he pushed the door of the pub open. ‘What about Africa for a nice villa and year-round sunshine?’

‘And long rolling warm sea waves,’ Mike murmured.

‘Morning, Pete,’ said the barman.

‘Two whiskys,’ said Pete.

‘Are all pubs like this?’ asked Mike, in disgust, at the sight of all the chrome and glitter.

‘No, there are still some old-world pubs in the country, {32} but with all the rebuilding that's been going on, the breweries decided to go ail-American, and turn pubs into bars.’

‘Two whiskys,’ said the barman, putting the glasses on the bar.

‘How much?’ asked Mike.

‘This is on me,’ said Pete to the barman.

‘Not at all, how much?’ said Mike.

‘One pound fifty-five,’ said the man. Mike almost whistled, but managed to control himself and paid for the drinks. They moved over to a corner table.

‘That's good,’ said Mike, sipping his drink.

‘Mike,’ said Pete thoughtfully, ‘you know, you mustn't rush back into your old way of life.’

‘Sorry?’ said Mike in surprise.

‘Look, you mustn't go around saying that you're back. People are going to think it's a funny business. What you've got to do is to slowly ease yourself back, almost as if you've never been away.’

‘I know. It's just that I'm really so excited to find that I'm a reality, I forget that it will seem strange to other people.’

‘Hmm. You know, your story still worries me?’ said Pete, finishing his drink and signalling the barman for two more.

‘Pete, the whole thing is just as alien to me as it is to you. What can I do about it?’

‘I don't know. If you looked forty-two instead of thirty-two, you could have any story you wanted, but it's the way you look.’

‘Therefore, I mustn't tell anyone what happened to me, just leave them guessing.’

‘Your drinks,’ said the barman, putting two full glasses down.

‘Thanks,’ said Pete, and waited for the man to leave. ‘You should write this up as a book.’

‘Christ, I was going to write this idea up as a TV programme, not as a personal experience.’

‘But what if it isn't?’ said Pete, looking earnestly at Mike.

‘What do you mean?’

‘You might be in limbo, between two living realities.’

‘Pete, do you still believe in reincarnation, and all that crap?’ laughed Mike.

‘You can laugh, and disbelieve, but there are greater things going on in this Universe than either you or I can understand.’

‘What about God? Where does He fit in?’ {33}

‘There's always good and evil in whatever one's talking about. God is the good image of the Universe.’

‘I'm not going to argue the point. We've talked around this subject for years, but as far as I'm concerned, I am normal flesh and blood, and that's substantial enough evidence for me.’

‘I hope you're right,’ said Pete, frowning.

Mike looked at the deep lines in the dark face. He'd always been fascinated by the supernatural, but he'd only looked on with objective interest. Pete, on the other hand, had become very involved. Mike again suddenly felt overwhelmed as the reality of his new-found world slowly vanished leaving him swimming in the middle of nowhere.

‘Hey man, take a look at what's just walked in,’ said Pete, breaking into Mike's thoughts. He turned to see two very elegant women walking into the pub. They went over to a corner table on the far side of the bar and sat down. Mike was just wondering whether he should go over and introduce himself, when he saw something that almost stopped his heart. Sitting at the same table was a very tall, very thin man.

‘The Professor,’ said Mike, under his breath.

‘What did you say?’ asked Pete, leaning forward.

‘You see the man sitting at the same table as those two women who just walked in? Well, I'm damned sure that's the Professor I was telling you about.’

Pete turned to study the table, and then turned back to Mike. ‘Are you feeling O.K.?’

Mike looked at Pete in amazement. ‘Of course,’ he said.

‘There's no one at that table except the two women,’ Pete said quietly.

Mike looked hard across the room. There was the Professor. ‘Are you looking in the right place?’

‘Sure, over there where the two peaches sat down.’

Mike shook his head and closed his eyes. He had to be dreaming. He opened his eyes to see Pete standing in front of him.

‘You don't look too well to me. Come on, I think a lie-down will do you good.’

Mike obediently got up from the table, and followed Pete. As they reached the door he looked back. There was no man. He looked quickly round the pub but the Professor wasn't anywhere to be seen.

‘I'm sorry, Pete, but I could have sworn that there was a {34} man sitting at that table who resembled the Professor,’ said Mike as they walked along.

‘Maybe you did, my eyes aren't as good as they used to be. Anyway, I don't think it would be a bad idea to go home, we both seem to be a little tired.’

Mike was about to protest, but if Pete hadn't seen the man, maybe he hadn't. If he hadn't seen the man in the flesh, then why should he suddenly see an apparition? Pete marched Mm into the flat and once inside pushed Mike into a chair.

‘Now listen to me, Mike. You obviously have had a nasty shock and maybe your mind is still confused by events, but for God's sake, pull yourself together. If you need a trick cyclist then I'll get you one, but you've got to live with the reality that ten years have gone by, and you can't explain it,’ said Pete, exploding with emotion.

‘Pete, I promise I won't mention the subject again,’ said Mike with a winning smile.

‘That's good, that's very good.’

Mike could understand Pete's fear. The experience he'd had couldn't be explained in rational terms. This only left the supernatural as far as Pete was concerned. Pete poured a couple of stiff Scotches and they drank in silence.

‘Well, I think I'll take a little nap,’ said Mike, feeling this might soothe Pete's disturbed mind.

‘Good idea, you put your feet up, and I'll just potter around for a while,’ said Pete, in a very fatherly way. Mike half finished his drink, and then collapsed on the couch. In his own mind he felt that the appearance of the Professor wasn't an apparition. It must have some meaning, but what?

Sue and the Professor. He must try to locate them both. His mind went on working away at the problem, until he fell into a light sleep.

Mike was awakened suddenly by the sound of someone screaming. He swung his feet off the couch, and looked round. Guy was standing by the front door one arm in her coat. Mike started to move towards her when he saw Pete, standing holding his head.

‘You're evil, you're bloody evil,’ yelled Guy. Mike turned round to Pete, who was now down on his knees. Then Mike saw it, hovering on the wall. The blob of light twinkled and sparkled like a small star. He heard the door bang. His mind filled with tiny darts of light increasing in intensity and he slowly crumpled to the floor in a dead faint. Pete tried to {35} struggle to his feet, but suddenly he screamed in agony. He hit the wall with a ferocity that snapped the bones in his body.

‘When in doubt, tell the truth.’

Mark Twain

MIKE woke with a king-size headache. It was so dark it took a few moments for his eyes to adjust. The floor was rough and cold. Mike raised himself on one hand, and looked around. He focused on the bare, shabby walls, and wondered where on earth he was. Far away in the distance he could hear the sound of heavy machinery at work and the occasional raised voice.

The room was suddenly exploded by an eye-splitting thump, and part of the outside wall caved in. Mike was instantly on his feet and grappling at the closed door as the large, menacing weight crashed in again. He pulled hard on the handle and it broke. The weight was swung out of the room. Mike moved back from the door and charged, hitting it hard. The demolition weight had distorted the frame. He pushed urgently through the gap he'd managed to make.

Outside was bright and airy. He was lucky. It was all too apparent that almost the whole building had gone except where he was standing. He heard shouts and looked down. Workmen below had noticed him and were waving frantically. The demolition weight came crashing closely alongside. It was an unhealthy place to be, and he hurriedly made his way through the rubble to safety.

‘What the hell do you think you're doing?’ shouted an irate workman, coming over to him.

‘Sorry, mate, I didn't know you were going to demolish the building,’ said Mike, taking a look around. There was nothing left of the street, and in the far distance he could see the green of Hyde Park. What the hell was he doing there?

‘All right, you'd better come with me,’ said a man in uniform. Mike was going to resist the invitation but, seeing the hard, stocky workmen standing close by, he decided {36} that passiveness was a good policy at the moment. They walked over to a neat hut. The uniformed man opened the door and Mike walked in.

‘What is it, Sid?’ said another man in uniform sitting behind a desk.

‘Found this fellow up on the landing of the house we're bringing down.’

‘Where we started work this morning?’

‘Right, he nearly got himself killed,’ said Mike's captor.

‘Rubbish,’ said Mike.

‘You keep your mouth shut until you're invited to speak,’ said the man, getting up from behind his desk. ‘You weren't trying to kill yourself, were you?’ he smiled.

‘Don't be stupid, why should I want to kill myself?’ said Mike in exasperation.

‘Funny, isn't the man funny?’ said the man, giving him a back hand across the face.

‘What the hell was that for?’ Mike said furiously, squaring himself up to the man. He was suddenly grabbed from behind and sat down hard on a seat.

‘What's your name?’ said Mike's attacker, going behind the desk.

‘Why?’ asked Mike truculently.

‘Because I need it. Funny men like you can't come walking onto my building site trying to kill themselves without being reported, dead or alive,’ came the reply.

‘I didn't come here to kill myself. You're mad, bloody mad.’

‘All right, so you weren't trying to kill yourself, what were you doing here then?’ said the man viciously.

‘I came back to visit an old, familiar building before it was destroyed,’ Mike said, inadequately, struggling to remember what had happened.

‘Oh, roll me over and tickle my tummy again, that makes me laugh. Sounds more like you were up to no good,’ said the man, taking up a pen.

‘Name?’

‘Jerome, Michael Jerome.’

‘Fine,’ said the man, getting up and putting on his jacket. ‘You'd better come with me.’ Mike was ushered out of the hut and the two of them made their way to the entrance of the site and to a row of small bubble-like cars. The man went up to the first one and opened the door. Mike got in. As the man walked round to the other side of the vehicle, Mike tried to find a door handle, but he didn't have enough {37} time. The man pressed a switch, let the brake off, and they were on the move.

Mike was sharply aware of the emptiness of the streets. It was uncanny. London streets were always an inferno of metal and noise.

They stopped and entered a police station. At the desk the man who had brought him pressed a button and a policeman appeared. He was dressed in a lightweight, blue uniform almost like army combat dress, and carried a gun.

‘Yes?’ said the policeman.

‘Found this fellow on the building site.’

‘Do you want to prefer charges?’

‘No, I'll leave him with you,’ said the man, moving towards a corridor. The policeman nodded and picked up a form and pen.

‘Now, sir, would you like to tell me what you were doing at the site?’

‘I don't really know.’

‘Right, your name please.’

‘Michael lerome.’

‘Address.’

‘I'm afraid I don't have an address at the moment.’

‘What were you doing on the site?’ said the policeman unperturbed.

‘I went back to have a look for an old friend, but I found that the whole street was being demolished,’ Mike said, stating the nearest thing to the truth. He leant forwards to see what the man was writing. The date at the top of the form confirmed his dread. It was 1989. Feeling dazed, he turned round to look for something to sit on.

‘Just a moment, Mr. Jerome,’ said the policeman, leaving the room.

Mike made for the door. He pushed hard on the glass doors but they wouldn't budge.

‘That's the entrance, not the exit.’ Mike turned to see a plain-clothes man standing behind the counter. ‘If you will come this way.’

Mike passed through a half-door in the counter, and looked hard at the pleasant face with its lines of worry running from the corners of the eyes. Mike felt very conspicuous alongside him. Everyone was wearing clothes made from light fabrics, with a military cut about them, whereas he was wearing his roll neck sweater and suede jacket. They passed through a large room which looked like a communications room. In a rabbit warren of passages, the man in front of him stopped. {38} Mike hesitated for a moment in the doorway, and was given a push from the policeman he'd first seen. This man slid the door shut behind him, leaving the plain-clothes man and himself. The room contained a semi-circular desk and two chairs. The man sat down behind the desk and motioned Mike to take a seat. Mike was unimpressed by the room; it was so stark it was uncomfortable. The detective read something that was in front of him and clicked a switch on the desk.

‘Sergeant, cross reference the fingerprints and let me have the file on Mr. Jerome, Mr. Michael Jerome,’ said the man, swinging round in his chair and looking out of the window. There was nothing of interest out in the yard, except for a grill in the ground to allow the water to drain away. The sergeant took Mike's fingerprints and went away.

‘There's nothing on him, sir.’ The sergeant had returned, nonplussed.

‘That's ridiculous. Mr. Jerome, can you remember when your fingerprints were taken?’

‘I think the last time that I can remember was when I got my New York driving license,’ said Mike, in all honesty.

‘No, I mean for the computer identification,’ the detective said testily.

‘I don't think I've ever had that done,’ came Mike's reply.

‘You must have, you wouldn't have a passport otherwise. Come to think of it, you wouldn't be able to do anything without this record being taken,’ said the detective, in firm disbelief.

‘There is some information on Mr. Jerome, sir,’ said the sergeant, handing over a very thin file. It was opened and studied. Mike sat there trying to think of any offences he might have committed, but nothing came to mind.

‘Well, Jerome,’ the detective said, his voice changing to a hard, official tone, ‘what were you doing on June 7th, 1979, and where have you been since that date?’

‘I was with a friend called Peter Jones,’ said Mike.

‘And what have you been doing since then?’

‘I don't know,’ said Mike truthfully.

‘Mr. Jerome, you are wanted by the police for questioning. If you won't tell me where you've been then I must assume you've been in hiding, otherwise you couldn't have avoided having your fingerprints taken.’

‘Not necessarily,’ Mike said, wondering what the devil they wanted to talk to him about.

‘Oh yes, every country in the world runs fingerprinting {39} computers, and I don't feel you could have avoided them, unless you were purposely hiding.’

Mike sat looking at the detective wondering what he could say.

‘Jerome, I'm waiting,’ said the detective, impatiently.

‘Well, all right,’ said Mike. ‘The answer to your question is very simple, I've been travelling through time.’