Why I Left

Canada

| {i} |

| {ii} |

Reflections on Science and Politics

Translated by Helen Infeld

Edited with Introduction and Notes by

Lewis Pyenson

McGill — Queen's University Press Montreal and London

1978

| {iii} |

© McGill — Queen's University Press 1978

International Standard Book Number o 7735 0272 6

Legal Deposit first Quarter 1978

Bibliotheque Nationals du Quebec

This book has been published with the help of a grant from the

Social Sciences Research Council of Canada using funds provided by

the Canada Council. It was translated from material in Sziice

przesziosci (Warsaw, 1964) and Kordian i ja (Warsaw, 1968) published

by Panstwowy Instytut Wydawniczy.

Design by Peter Maher

Printed in Canada

| {iv} |

Acknowledgements viii |

Introduction by Lewis Pyenson 1 |

Canada 17 |

Poland 55 |

Bronia 123 |

Konin 130 |

Einstein 136 |

Oppenheimer 160 |

The Centenary of Max Planck 181 |

Notes 189 |

Index 205 |

| {v} |

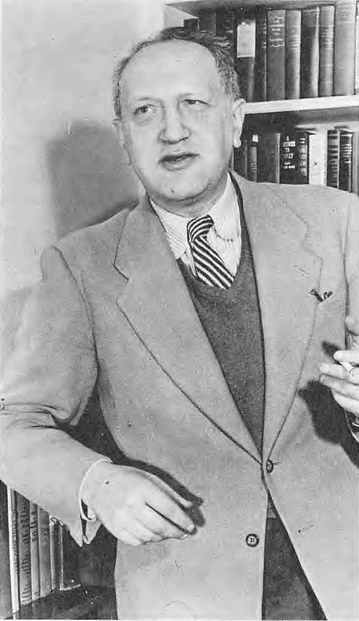

Frontispiece Leopold Infeld

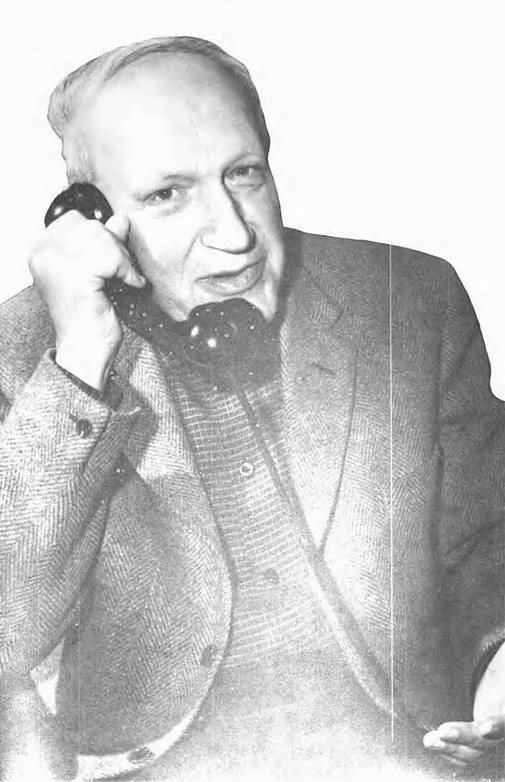

1 Leopold Infeld in Princeton. Photograph by Lotte Jacobi. 16

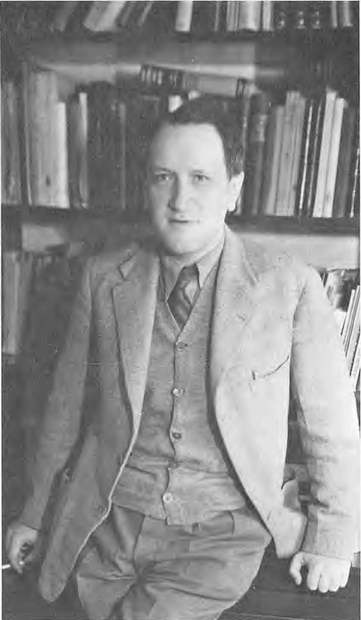

2 Leopold Infeld in Toronto. Photograph by Gilbert de B. Robinson. 27

3 The Infeld family in Warsaw 1950. Photograph by Central Photographic Agency, Warsaw. 62

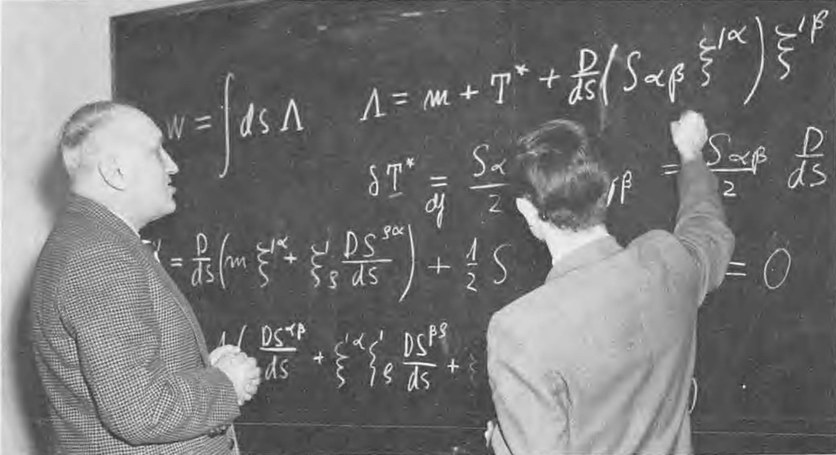

4 Leopold Infeld with a student in Warsaw. Photograph by Central Photographic Agency, Warsaw. 68

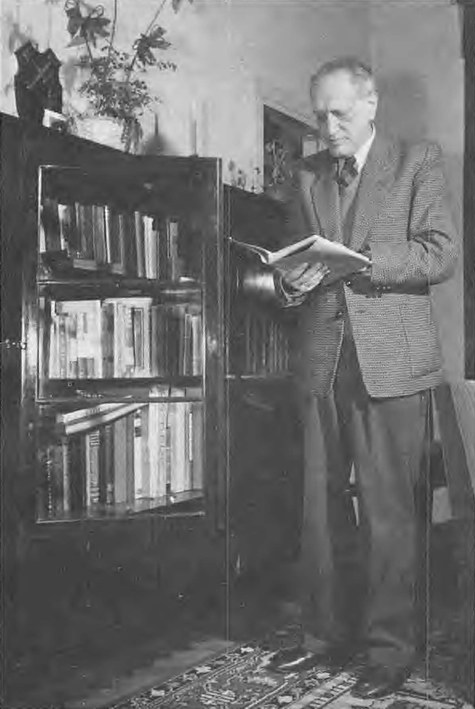

5 Leopold Infeld at home, about 1954. Photograph by Central Photographic Agency, Warsaw. 76

6 Leopold Infeld at the weekly seminar of the Institute of Theoretical Physics, Warsaw. Photograph by Jan Mkhlewski. 81

7 The Infelds with Chou En-lai in Peking 1955. 98

8 The Infelds with Cecil Powell (left) and Joseph Rotblat at the Pugwash Conference in Prague 1964. 102

9 P. A. M. Dirac, Andrzej Trautman, and Leopold Infeld at the International Gravitational Conference 1962. Photograph by Marek Hohman. 106

10 Leopold Infeld with Hermann Bondi at the International Gravitational Conference 1962. Photograph by Marek Hohman. 110 {vi}

11 Albert Einstein and Leopold Infeld. Photograph by Lotte Jacobi. 138

12 Peter G. Bergmann, Albert Einstein, and Leopold Infeld. Photograph by Lotte Jacobi. 157

13 Indira Gandhi and Leopold Infeld 1963. 163

14 Tenth Washington Conference on Theoretical Physics 1947. Photograph by Charles U. Holbrook. 166

15 Leopold Infeld 1898–1968. Bust by Melberg. 186

| {vii} |

Among those who helped in various ways with this edition of Leopold Infeld's later writings are H. S. M. Coxeter, Eryk Infeld, James MacLachlan, Alfred T. Mitchell, Susan Sheets-Pyenson, Christie Vance, and Peter White. Maria Jastrzebowski verified the translation typed by Lucyna Piatek. Margery Simpson of McGill-Queen's University Press and Barbara Borkowska and Andrzej Mierzejewski of the Polish Authors' Agency provided prompt and sensitive editorial assistance. Otto Nathan and Helen Dukas authenticated extracts from the letters of Albert Einstein, and the Estate of Albert Einstein has generously consented to the publication of this material.

While this book was in press notification was received of the sudden death of Leopold Infeld's friend and colleague Alfred Schild. An expert in relativity physics, he followed this edition of the writings of his former teacher with interest. By a sad twist of fate, it was not given to him to see the finished product.

| {viii} |

When I first met Leopold Infeld in January 1942, he had been in Toronto for three and a half years and had made it his home. Wherever he was he could come to terms with his surroundings and make his presence felt whether in a room or a city. I became at the same time Leopold's student and friend. He never treated me as a subordinate in spite of the differences in our position and age. We were both interested in asking new questions and searching our minds for new answers. In this we were equal. Of course he knew far more than I, and his brilliant and penetrating intellect greatly influenced my life during the next few years.

We met almost daily to work together, far more often than is common in a professor-student relationship. At most of these meetings he would outline his latest approach to our current problem. With great enthusiasm he would explain that a new perspective had dissolved all our difficulties and that the solution was childishly simple. {ix} Then we would examine his arguments and his premises and eventually reach the flaws. He always came up with another idea. We moved forward, found the flaw, and moved back, but never quite back to the beginning; and so our work advanced by thrust and check and thrust again. Sometimes this took place as we walked in the university grounds. Often we went to his house and then spent an hour or two in his study. Helen would bring coffee and, when his own daily quota of cigarettes was consumed, we would smoke the handmade cigarettes which my wife Winnie had rolled that morning.

Leopold's work in physics occupied a large part, but not all, of his life. He enjoyed his family and his friends. There was nothing of the hermit in his makeup. He had an appetite for life and a curiosity about everything. He liked to gossip, to eat and drink, to discuss the world in all its aspects.

He and Helen naturally formed the centre of a lively intellectual group. Both expressed and defended their opinions with vigour, but they also kept their minds open and liked to discuss and consider the ideas of others. Their influence spread far more widely than that of the average university couple. There was something magnetic, even exotic, about the big, talkative, brilliant man and his equally intelligent and attractive wife. Toronto in those days was a rather provincial city, its spirits dampened by a long and bitter war. It was not a lively place and Infeld says in Quest: “It must be good to die in Toronto. The transition between life and death would be continuous, painless and scarcely noticeable in this silent town.” But Leopold made his own excitement; he refused to settle down into a dull daily routine.

People who will not accept the status quo and want to change the things they feel are wrong in the world must often suffer indignities from those who sit smugly in their comfortable corners and feel that any change threatens their position and their self-image. It was the Infelds' fate, during their last year in Toronto, to suffer at the hands of the smug and the fearful. Why I Left Canada understates, I think, the deep hurt Canada inflicted on this humane and decent family. Mean and vicious people made their last days there miserable. Remembering the kindness and friendship they had enjoyed for a decade, Leopold left the last shabby Canadian chapter unwritten. He writes of the official, public attacks but not of the private campaign of harassment, often by anonymous phone calls, of which, even today, Helen speaks with bitterness. {x}

And so they left Canada to help Poland in its tremendous struggle to rebuild and to rise again from the ashes Germany had left.

In the fall of 1959 Andrzej Trautman, Bill Thompson, Winnie, and I were waiting at the London airport for the Infeld's flight from Warsaw. Leopold had suffered a serious heart attack a few years before, and they were coming to England for Leopold's periodic medical check up. Winnie and I had not seen them for almost ten years. It was a shock to see Leopold's ashen face, to watch his halting walk aided by a cane, to hear his slow and slightly slurred speech. But after a short time we realized with great relief that his spirit had not changed at all.

Later, during a visit to Warsaw, Leopold told us that soon after the onset of his illness he had decided that any day his heart might stop, but that until that day came he would live as fully as he could. He had to give his body some attention—a nap every afternoon, a saltless diet, the pills which prevented the accumulation of water in his cells; but apart from these necessary precautions he refused to treat himself as an invalid. He might just as easily die in Warsaw as die abroad, he said. In the last nine years of his life, the Infelds travelled to several places outside Western Europe, to India, Texas, Greece, and Israel. In all these countries Leopold enjoyed observing new customs and making new friends.

Leopold Infeld was a distinguished theoretical physicist. During a short visit to Leipzig in the early thirties, he and van der Waerden wrote an important paper on the generalization of the spinor calculus and of Dirac's equation for the electron to general relativity theory. In 1934, he was awarded a Rockefeller fellowship to work at Cambridge. There he collaborated with Max Born on what is now known as the Born-Infeld theory. It was an attempt to explain the existence of elementary charged particles in terms of well-behaved solutions of nonlinear equations for the electromagnetic field.

In 1936 he accepted a research appointment at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. He worked with Albert Einstein and Banesh Hoffmann on the equations of motion in general relativity, a problem which was to be his principal research interest for the rest of his life. The work showed that Einstein's theory of gravitation has a unique feature, that the field laws alone determine the motion of particles and that no independent laws of motion are needed. This beautiful result is intimately connected with the nonlinearity of the {xi} gravitational field equations. It should play an important part in the future development of the whole of theoretical physics. The work also gave the first satisfactory description of the motion of several particles in gravitational interaction, for example, the relativistic motion of a double star. In 1960, Infeld and his former student Jeray Plebariski published a treatise on the subject, Motion and Relativity.

As important as his own scientific achievements was Leopold's success as a teacher. He attracted some of the brightest young men to work with him, and many of his research students and his students' students now hold university professorships, particularly in Canada and Poland. This ability to bring out the very best in his younger collaborators was due, I believe, to a strong feeling of his own worth combined with an equally strong respect for the worth of others and for the integrity of their individual views. I remember vividly and with gratitude two pieces of advice he gave me when I was completing my Ph.D. work: “Be generous to your students and be generous in giving them credit for their work; always try to gather around you those whom you think better than yourself.” Leopold practised what he preached.

Leopold was convinced that it was the duty of scientists and other intellectuals to concern themselves with the state of the world, to make moral judgments, and to speak out openly on public issues. Again he practised what he preached, and often this took a great deal of courage. In Canada he spoke in favour of the post-war communist government in Poland at a time when such views were highly unpopular in the West. In Poland he led a movement of scholars and scientists for greater personal and intellectual freedom at a time when it was dangerous to express such views openly. He was one of the original signers of the Einstein-Russell manifesto of 1955 which led to the Pugwash Movement on Science and Public Affairs, an historically important step on the road to restraint and perhaps to nuclear disarmament.

Peter Bergmann concludes his obituary of Leopold Infeld in Physics Today by saying: “With his death all of us lose a distinguished colleague, and many a wise friend.” I know that Winnie and I and our children feel this keenly, and we miss him.

Alfred Schild

Austin, Texas

| {xii} |

By a series of strange circumstances-, I did not become a leather merchant in Cracow and I did not die during the war in the ghetto of Cracow as did most of my family and almost all of my friends. This is due more to my luck and character than to my ability.

Leopold Infeld, “As I See it.”

Like others of his generation who became great scientific or intellectual figures, Leopold Infeld issued from central Europe at the time of material transformation and rising expectations that led into the twentieth century. It is not the intensity of Infeld's struggle to become a theoretical physicist, succeeding against all likelihood, that is striking in his own accounts; many others to whom events were less kind may {1} also claim to have contributed to human understanding. Neither is Infeld's talent as one of the most perceptive inside observers of twentieth-century theoretical physics unexpected, even if noteworthy in an age of mediocre autobiographical apologies by other scientists. Rather, most extraordinary in Infeld's final vision is his compelling faith in humanity.

Infeld was born in a Jewish ghetto in Krakow in 1898. His father was wealthy enough to keep a servant for the family's modest apartment. After having been educated in a Jewish commercial school, Infeld persuaded his parents to let him prepare for the university entrance examinations. These he passed on the eve of the First World War. After his father had bribed local officials to release him from active service in the Austrian army, Infeld could regularly attend lectures in physics at the Jagiellonian University in Krakow. He received his doctorate from Krakow in 1921 as the Polish Republic's first theoretical physicist.

Upon graduation Infeld had no prospects of employment. A few chairs in theoretical physics existed at Polish universities, but these political appointments were in practice closed to Jews. In his essay on Wladyslaw Natanson, which is translated in this book, Infeld remarks on the restrictive system of academic succession:

To attract students, to train them—this was looked upon in old Krakow as vulgar, smacking of the kindergarten. It was considered proper to select one student during a lifetime, make him a docent, and let him wait quietly for his professor to retire or die. In order that he might wait not too impatiently, he should be a person of some means, politically reliable—which meant a Krakow conservative—and be of good family. If such a person has already been found, then Pauli's exclusion principle applies: the place is filled and no one else can aspire to it.1

Infeld spent the next years as a schoolmaster in the provinces and then in Warsaw. He managed to be appointed assistant and finally docent at the University of Lwów. In 1933, following the death of his wife Halina, he obtained a Rockefeller fellowship to study at Cambridge with Max Born and at Leipzig with Bartel L. van der Waerden. Returning to Poland and finding no possibility of succeeding to a chair, he left in 1936 to work with Einstein at the Institute for Advanced Study in {2} Princeton. This voyage marked the beginning of a thirteen-year absence from Poland.

In 1938, at the age of forty, Infeld was offered the opportunity to begin a new career at the University of Toronto. His autobiography Quest reveals that he received this call with mixed emotions.2 He was beginning his career once more at a time in life when many other theoretical physicists hold chairs and have their best work behind them. Infeld was promoted rapidly and trained many students. Despite the presence of brilliant mathematical colleagues, however, his own speciality withered. His Department of Applied Mathematics merged with the Department of Mathematics. The University of Toronto expressed little interest in Infeld's desire to create a strong centre of theoretical physics.

Canadian indifference to theoretical physics reflected broader trends. Though theoretical physicists were active elsewhere, this discipline was not favoured by many of its host institutions. Before the Second World War physics remained the only scientific discipline to have produced a speciality devoted exclusively to theory. Theoretical physicists sought to provide a framework for unifying the laws and phenomena discovered by many widely separated research programs.3 Since the time of its creation, theoretical physics represented only a small part of the educational effort in science. In Germany, where the discipline first established roots, fewer than 7 percent of all doctorates granted in the years around 1900 went to physics; only a small fraction of these were in theoretical physics.4 Though of increasing relevance for other disciplines, theoretical physics remained relatively neglected in a period that saw the rise of large-budget research teams in experimental physics.

As a rare theoretical physicist training doctoral students in Canada, Infeld was discouraged. Nevertheless, disciplinary isolation was not behind his decision in 1950 to leave Canada for Poland. Infeld was sympathetic to the new Workers' State in Poland; he extensively denounced American nuclear blackmail; he collaborated closely with Einstein. Stimulated by McCarthyism in Washington and by the Gouzenko affair in Ottawa, conservative critics denounced Infeld as a potential traitor to the Canadian people. The leader of the opposition asked, if Infeld were permitted to go to Warsaw University in 1950 to lecture during a leave of absence, as he planned, would he not {3} provide the communists with atomic secrets? As with many others in North America, Infcld received too little help too late. RCMP surveillance and other harassment made it impossible for him to continue his research. He decided to accept the Warsaw invitation, realizing that he might never be allowed to return to Canada. When he arrived in Poland, the Canadian ambassador asked him to surrender his Canadian passport. Later, his two children were stripped of their Canadian citizenship by an order in council, the only time such a procedure has ever been applied to native-born Canadians.

Infeld is Boswell for the mature Einstein, the wise old lion who seized the imagination of our age. In 1936, Infeld saw Einstein in Princeton again, after many years of separation. In two paragraphs he presents perhaps the fullest, most beautiful portrait of Einstein in his late fifties:

I knocked at the door of 209 and heard a loud “herein.” When I opened the door I saw a hand stretched out energetically. It was Einstein, looking older than when I had met him in Berlin, older than the elapsed sixteen years should have made him. His long hair was grey, his face tired and yellow, but he had the same radiant deep eyes. He wore the brown leather jacket in which he has appeared in so many pictures. (Someone had given it to him to wear when sailing, and he liked it so well that he dressed in it every day.) His shirt was without a collar, his brown trousers creased, and he wore shoes without socks. I expected a brief private conversation, questions about my crossing, Europe, Born, etc. Nothing of the kind:

“Do you speak German?”

“Yes,” I answered.

“Perhaps I can tell you on what I am working.”

Quietly he took a piece of chalk, went to the blackboard, and started to deliver a perfect lecture. The calmness with which Einstein spoke was striking. There was nothing of the restlessness of a scientist who, explaining the problems with which he has lived for years, assumes that they are equally familiar to the listener and proceeds quickly with his exposition. Before going into details Einstein sketched the philosophical background for the problems on which he was working. Walking slowly and with dignity around the room, going to the {4} blackboard from time to time to write down mathematical equations, keeping a dead pipe in his mouth, he formed his sentences perfectly. Everything that he said could have been printed as he said it and every sentence would make perfect sense. The exposition was simple, profound and clear.5

Infeld is most successful in describing the values Einstein brought to his work. Infeld's Einstein, though he came to lose confidence “in the merit of ever impressive confirmations of theories, whenever questions of principle are involved,” still claimed “strict adherence to logical simplicity.”6 Einstein's tools came from mathematics. As a young man, he thought that mathematics was at best incidental to the development of new syntheses of nature's laws. Later, after having formulated the covariant field equations of general relativity, he came to believe that mathematics might provide a heuristic basis for new physical theories. Nevertheless, through Einstein's entire scientific career runs the thread that mathematics was insufficient to dictate the nature of physical reality. “God does not care about our mathematical difficulties,” Infeld cites Einstein in Quest, “He integrates empirically.”7 Mathematics for Einstein constituted a language which had always to be used and then transcended before truth could be fathomed. He wrote to Infeld in 1946, “Please don't be angry with me that I have written you so infrequently; the devilish passion to find a solution for these most difficult problems has held me pitilessly in its clutches and has forced me to make desperate efforts to overcome the mathematical difficulties.”8 The tendency was great, Einstein felt, to use mathematical formalism as a substitute for knowledge. Physical intuition, the sixth sense Einstein mentioned in his Autobiographical Notes, remained the key to understanding.9

Central to Infeld's narrative is the intensity and clarity of Einstein's intellectual power. “There is a most vital mechanism which constantly turns his brain. It is the sublimated vital force. Sometimes it is even painful to watch.”10 This characterization derived from several years of close collaboration on the nature of motion in the general theory of relativity. The result of Infeld's and Einstein's work, well known among specialists in field theory but not widely popularized, was truly a joint effort, as Einstein himself insisted later.11 It is also perhaps the episode in Einstein's creative endeavour that is best documented. {5}

Einstein had suggested a common project that involved deriving the equations of motion from the gravitational field equations, and, in addition, uniting the gravitational and the quantum theories. This proposed course was to be a major innovation, for in the general theory of relativity the motion of mass points was governed by geodesies in space-time, and the metrics were derived separately from the field equations. In the period between 1936 and 1938 Einstein and Infeld worked on these problems together, frequently at each other's side for entire afternoons. Infeld was skeptical at first about both of Einstein's contentions, and he luxuriated in his own contrariness. A critical attitude and an independent spirit were essential if his collaboration with Einstein were to succeed. Infeld recalls in Quest:

I know that there is nothing so dangerous in science as blind acceptance of authorities and dogmas. My own mind must remain for me the highest authority. Nearly every understanding is gained by a painful struggle in which belief and disbelief are dramatically interwoven. I wanted to make this point quite clear to Einstein.12

When Infeld first came to believe intuitively that the equations of motion were indeed contained in the field equations, his whole attitude changed, and he began to work with great enthusiasm. But he still doubted that the field equations could be related to the quantum theory. Skepticism formed the basis of his contribution to the joint effort, for, at last, he was able to convince Einstein that the gravitational equations could not yield quantum restrictions for motion.13

The collaboration was enormously difficult for Infeld. He felt constantly submerged in a flood of new ideas. “Sometimes after we separated I would think in the night about our last discussion, and a new idea would strike me, illuminating the subject from a new angle. Next day I would rush to Einstein, often only to find that he had come to the same conclusion and was still further along.”14 Once the general theory was established, specific calculations had to be undertaken. This was Infeld's task. Although Einstein was interested in the difficulties that appeared, he took little part in the actual work. Einstein believed that the essential part of the problem had been solved. “Once a work is finished,” Infeld remarks elsewhere in Quest, Einstein's “interest in it ceases.”15 {6}

The collaboration of Einstein with Infeld came to provide the focus for both their lives. At the time they were working, Einstein's wife Elsa was in the terminal stage of her last illness. The first floor of the Einstein residence had been arranged for her deathbed. On the second floor, in the study, Einstein and Infeld would work for many hours together. Einstein cared deeply for his wife, but death was something he knew he could not change. The pursuit of his work was his reason for being, and only in this way, by directing himself to what he believed to be fundamental, did he feel that he could cheat death. In Quest, Infeld describes how, after Elsa died, Einstein, more pale and more tired than before, continued to work mornings in his office. Recalling the death of his own wife Halina, Infeld marvelled at Einstein's composure.

Nearly a decade afterwards, in the late forties, Einstein and Infeld worked together once more. Einstein was almost seventy. During the war, Infeld had worked on problems unrelated to general relativity and had spent much time popularizing science. The two theoretical physicists had not seen each other for nine years. At Einstein's suggestion, they began to work again on the problem of motion in general relativity. Einstein wanted to demonstrate that the approximation technique they had developed could be extended indefinitely. The initial stages of collaboration were carried out by an intense correspondence. Then, Infeld relates, he thought of introducing a virtual gravitational dipole to facilitate the calculation. When he convinced his former student Alfred Schild that the approach was feasible, Infeld wrote to Einstein, who responded by explaining his own ideas without mentioning the dipoles. Infeld answered by criticizing Einstein's work and asked him to reread his letter explaining the dipole method. This time Einstein answered favourably:

You are quite right with your objections to my remarks about the divergence of the approximating equations. I write you only today because I had still hoped to find the letter in which you had offered some proof for your theories. But I was not successful. I had not read your letter with sufficient care because I had no doubts about the justification of my own thoughts which were based on breaking down the Bianchi identity. And so I should like to ask you to send me a copy of your remarks.16 {7}

Einstein, sure that his way was more fruitful, had lost Infeld's letter. Infeld decided that a visit to Princeton would clarify the matter. The meeting actually took place in a New York clinic where Einstein was under observation and treatment. Einstein sensed that he would not live much longer. Infeld deferred to his collaborator:

I knew Einstein well and I knew that it didn't do to interrupt him. He talked about the trouble he still had with his work. Apparently he had completely forgotten my letter. When he finished I asked him to let me explain how I believed I had overcome the difficulty. I got out only two sentences—about the fact that it is necessary to add the gravitational dipoles, that they guarantee the integrability of the equations and that the later removal of the dipoles gives the equations of motion. As always when he was thinking, he began to stroke his moustache and then ask questions. I knew that this was his method, that he did not like lectures, only discussion. When I had answered three questions Einstein exclaimed enthusiastically, “Well, then, our problems are solved. Why didn't you write me about it?”17

Einstein pursued his work with singleminded purpose.

The quality that Einstein dearly sought in collaboration, as in friendship, was obstinate criticism. It was precisely this quality that Einstein valued in his early collaboration with Jakob Johann Laub and Erwin Finlay Freundlich, in his friendship with Paul Ehrenfest, and in his work with Infeld.18 Einstein loved Infeld for his ebullient, critical approach to theoretical physics. The spirit Infeld brought to his work was uncharacteristic of that radiated by many other professors. Infeld's world was far from the academic bourgeoisie.

As Infeld was aware, considerable moral and emotional strength was required to work as an intellectual in Wilhelmian or Weimar Germany and not appropriate at the same time the usual worldviews endemic to German academic society. Deciding to become a non-establishment intellectual carried the possibility of being frozen on the periphery of academic life in German-speaking and Eastern Europe. Infeld points out that even unusual powers of self-reliance were often not enough to prevent a disastrous erosion of self-confidence. Einstein working at the Patent Office in Berne, Laub as an unemployed physicist in Wurzburg, Ehrenfest without a position in Russia, Infeld as a schoolmaster in Konin, all were theoretical physicists on the {8} periphery of the physics profession. Although they were for a time outsiders in a highly structured discipline, it would be a mistake to claim that Einstein and his close friends belonged to an alternative culture.19 They were not science-oriented bohemians, nor were they social revolutionaries like the astronomer Anton Pannekoek, the mathematician Gerrit Mannoury, or the philologist Rudolf Grossmann.20 Unconventional philosophical socialists, whose belief in social justice and critical thought were both paramount, comes closer to the mark.

At the time he collaborated with Infeld, Einstein sensed that most professional physicists regarded him as a ridiculous figure. Only a handful of people would bother to read Einstein's latest papers, Infeld remarks. Why, then, should Einstein's enterprise have seized with such force the imagination of an age? Infeld suggests that Einstein's renown appeared as a manifestation of social psychology after the First World War. The verification of general relativity by the Royal Astronomical Society expeditions of 1919 reflected “abstract thought carrying the human mind far away from the sad and disappointing reality.” Predicted by a German scientist and confirmed by English astronomers, general relativity seemed to indicate a new era of cooperation.21 Infeld believes that Einstein's fame persisted because of a popular image that remained true in its essentials:

Everything that Einstein did, everything for which he stood, was always consistent with the primary picture of him in the mind of the people.... He was like a saint with two halos around his head. One was formed of ideas of justice and progress, the other of abstract ideas about physical theories which, the more abstruse they were, the more impressive they seemed to the ordinary man.22

In his Autobiographical Notes Einstein remarks that he was, to use Infeld's imagery, a secular monk contemplating the extrapersonal world.23 Evidence for any duality in his spirit is lacking. Infeld remarks later that Einstein had always believed that scientific work was “a matter of character.”24 Einstein's science was a profoundly moral undertaking. Beauty, truth, goodness, justice—these are the interchangeable attributes of Spinoza's god, and perhaps in their relatedness lay the unity of Einstein's genius.

| {9} |

In 1937 Infeld's fellowship at the Institute for Advanced Study had expired and he faced returning to a darkening Poland. Although Einstein intervened on his behalf, Infeld could not obtain an extension of his appointment. To earn enough money to stay at Princeton for another year, Infeld suggested to Einstein that they write a popular history of physical thought for English-language readers. As the work progressed, it became increasingly less popularly oriented. The first part of the manuscript outlined the “new and revolutionary ideas” introduced into physics during the last half of the nineteenth century by Michael Faraday, James Clerk Maxwell, and Heinrich Hertz. In the second part, Einstein and Infeld described “the break brought about in science” in the twentieth-century that “gradually gained clarity and strength.”25 Emphasis was placed on the logic of physical developments, Einstein and Infeld recognizing at the same time that contemporary physics was characterized by major conceptual discontinuities. Completed without a title the manuscript became The Evolution of Physics: The Growth of Ideas From Early Concepts to Relativity and Quanta, through a compromise between the authors and the American publisher.26 At the time Einstein remarked to his friend Maurice Solovine that a more appropriate title for the book was the one used in the 1938 German translation that was published in Leiden,27 Physics as an Adventure in Understanding.28 Einstein believed the German title emphasized the psychological, subjective aspect of his and Infeld's story. The word evolution is out of place in the English title because the book explains revolutionary developments in nineteenth- and twentieth-century physics. Einstein and Infeld's English reader was led to expect a respectable story describing the regular progress of physical ideas.

Three years later, Infeld used the word evolution in the subtitle of his principal literary achievement, his autobiography. Despite the breaks and reversals of his career, he wanted to emphasize the continuity of his own individual experience. Quest: The Evolution of a Scientist chronicles his unusual apprenticeship. Justification of his scientific accomplishments was of minor importance in Infeld's conception of the work. He sought above all to relay his doubts, confusions, and daily impressions about the science and politics that he had {10} experienced in Europe and America. Quest ends with the discovery of Leopold Infeld on the verge of a new beginning in Toronto. The autobiography tells only part of his life. Some of his later experiences are relayed in the present book.

Quest is a remarkable achievement, a literary statement made the more compelling because it is written in Infeld's fourth language. It marks the beginning of a new role for the scientist as a writer. Before Quest, scientific autobiography as a genre was often little more than scientific apology. After obligatory references to youth and family, the author described his life as a confluence of scientific ideas, scientific influences, and scientific accomplishments. Nineteenth-century English autobiographies, for example, those of Charles Darwin, Thomas Henry Huxley, Alfred Russel Wallace, Herbert Spencer, and Charles Babbage, provide vivid insight into how Victorian scientists projected respectable images. Their creative psychology is retrievable only indirectly. In a similar way, many of the autobiographies that appeared in early twentieth-century Germany, those of Wilhelm Ostwald, Wilhelm Wien, and August FoppI, are really memoirs. The reader is presented with an image of the German academic as a cultural leader and member of the bourgeoisie. In both the English and the German cases, interaction between author and reader is one-dimensional. The literary medium is used to transfer a well-prepared picture rather than to moderate between author and reader.

Although Infeld was not the first to emphasize psychological development in autobiography, Quest is one of the first successful treatments of this kind by a scientist. Infeld's achievement is revealed by contrasting Quest against two other autobiographical attempts. The first is to be found in the posthumous memoirs of the mathematician Sonya Kovalevsky j the second, and an alternative pole of reference, is the autobiography of Henry Adams.

Kovalevsky's account is predictable and conventional.29 It offers no indication that the Russian noble's daughter, whose emotional lines are so carefully revealed, will become the greatest woman mathematician of the nineteenth century. Kovalevsky chooses not to speak of intellectual affairs. The reader is left without a clear idea of the narrator's vision of herself, in contrast to Infeld's doubt-ridden narrative. The Education of Henry Adams illustrates the pole opposite to that presented by Kovalevsky: transcendental reflections on society as {11} it impinges upon and subtly, continuously transforms the author's ego. Henry Adams offers possibly the most important statement about science and society to be delivered on the eve of the special theory of relativity and quantum physics.30 Central to Adams' text is the enormous emotional gap separating the “virgin” of humanism and faith from the “dynamo” of science and technology. Adams is one of the last premodern men, anticipating the intellectual, social, and political upheavals of the twentieth century with wonder and hesitation, but without fear. It is just this other-worldly teleology—Adams' detachment from the events that gently cajole his mind's eye according to some unspecified, internal, absolute mechanism—that the reader identifies as incomplete.

Transcending the difficulties posed by both Kovalevsky and Adams, Infeld's Quest lies near the beginning of a new literature. The autobiographical writings of such figures as James Watson and Werner Heisenberg follow, more or less directly, in Infeld's path. In presenting his story, Infeld brings the theoretical physicist down from the clouds. He is seen as an ordinary man, with ordinary wants and vanities, who seeks to fathom the laws of the physical universe. He is driven to his career in the same way that the artist or the writer is driven to his task. To work in theoretical physics Infeld sustains injustice and poverty. He pursues his science at the same time that his world—the world that made the discipline of theoretical physics possible—slides into barbarism.

Infeld's self-quest is continued in several of the essays constituting the present book. It may be better understood in contrast to the autobiographies of Sigmund Freud and Albert Einstein, whose work influenced Infeld's career. The reader is struck by the extraordinary singleminded purpose in the stories of Einstein and Freud. For either one to have recounted events irrelevant to his life's work would have been to disappoint the reader and ill serve his own cause. The process of stripping the author's persona to reveal his deeper self is at once continuous and complete. For Freud, creator of modern psychoanalysis, anything other than his moving intellectual history would be anticlimax.31 Einstein insisted on a similar position. A third of the way through his Autobiographical Notes, Einstein suddenly says: “the essential in the being of a man of my type lies precisely in what he thinks and how he thinks, not in what he does or suffers.”32 Nothing {12} would have been farther from Einstein's spirit than for him to have detailed the everyday occurrences of his youth, his emotional needs and strivings.

Freud and Einstein present convincing self-told stories because of who they are, and, indeed, because they detail the genesis of self-consciousness while omitting triviality. In their cases, unlike in Infeld's, the distinction between intellectual and psychological components is not of central importance for the reader. Their narratives are complete and consistent without telling about their reaction to everyday affairs, and for this reason the reader finds them remote and awe-inspiring. On the contrary, Infeld tells what it is like to be a theoretical scientist. The reader breathes with him as he walks through Princeton, Toronto, and Warsaw. Even Infeld's occasional vanities and failings only serve to bring about a more sympathetic rendering of the theoretical scientist at mid-century.

Presented in this volume are the later reflections of Leopold Infeld. The chapter “Oppenheimer” is taken from Kordian i ja (Warsaw, 1968). The rest comes from Szkice zprzeszhici (Warsaw, 1964). The chapter “Einstein” has been shortened somewhat in translation, as parts of the original text were adapted from Infeld's autobiography Quest (Garden City, N.Y., 1941). One long sequence from “Einstein,” where Infeld describes the Polish and Soviet reaction during the early 1950s to his work with Einstein, has been included in the chapter “Poland.” With these exceptions the translations correspond precisely to the original material.

| {13} |

| {14} |

|

plate 1. Leopold Infeld in Princeton. |

| {15} |

I well remember the shabby, small, two-story building at 47 St. George Street in Toronto. It has since been torn down. But then, twenty years ago, it still stood, uncared-for, unrepaired for many years. It housed the Department of Applied Mathematics—that is to say of Theoretical Physics—of the University of Toronto, where I spent the years 1938 to 1950. On the ground floor was a small lecture room. One flight up was the office of the head of department which was also used for conferences. Above this, under the roof, was my room. In addition, the building contained three offices of the other professors and small cubbyholes for the assistants. This department had originally been set up especially for its head, J[ohn] L[ighton] Synge, who had been at Trinity College, Dublin. He was more talented as a mathematician than as a physicist. Approximately my age, he was widely known and highly esteemed for his great industry and mathematical ability. It was known to happen that after an evening's discussion he {17} would come in the next day with a work all written up, neatly and without mistakes. A Fellow of the Royal Society of London, he was an excellent lecturer (and no doubt still is) and had an extremely upright, if somewhat dry, character.

In Canada we felt the war very little. Restaurants functioned almost normally; prices rose only a little; there was plenty of everything and the one evidence of the war was the appearance of enlisted men in uniform. British evacuees brought with them tales of falling bombs and sleepless nights and the very few refugees from Poland, who came through the Soviet Union and Japan, told about the suffering of my native land and its people.

Professor Synge and I discussed how we might help the war effort. He went to Ottawa to see General McNaughton, who had been the head of the Canadian armed forces during the First World War and then was the head of a scientific institution in Ottawa called the National Research Council. General McNaughton handed him some old notes taken during the First World War, giving many different kinds of figures on artillery fire, and asked that we put them in order and make a mathematical analysis of the material. Together with several other colleagues, we set to work. We met every Saturday and tried to find a formula to fit the given values. Several months later we completed the job and wrote a report in which we analysed the outdated information. Professor Synge sent it to General McNaughton. We were all sure that the report would be thrown straight into the wastepaper basket.

It happened that two or three years later I met a former student of mine who was then a lieutenant in the Canadian Army, and he told me that our work had been printed in a semi-secret publication. And that was not the end of the story.

Sometime later, I attended a dinner where General [Andrew George] McNaughton gave a speech, after which a mutual acquaintance introduced us. Searching for a topic of conversation, I said that I was one of the authors of the work done with Professor Synge. The general was very pleased to hear this and told me that he had learned from a Soviet general that this work was the basic ballistic study in the Soviet Army. Moreover, McNaughton told me that by our work we had saved many lives. When I reported this to {18} Professor Synge, he, like me, hesitated to believe that our analysis of outdated figures could have saved a single life.

When the “phony” war came to an end, the National Research Council asked us to undertake war work. We had a meeting in Ottawa —several scientists including Synge and myself, and high army dignitaries. After dinner we were scheduled to visit an army research centre. That day, Professor Synge told me that it might be better if I returned to Toronto and not waste time looking at laboratories. I found this odd suggestion hard to understand. Finally, Synge said hesitantly, “I can't lie to you—I must tell you the truth.” It turned out that I had not been “cleared” by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. I was sure that the reason for this was my left-wing views but Synge informed me that the Colonel who talked with him said it was because I had relatives in Poland. True, I was a Canadian citizen, but, should the Nazis wish to obtain secrets from me, they could do so by torturing my family.

Yet a few months later I was cleared and took part in the theoretical work on radar wave guides, this being the one field in which I ever had information that was at any time secret. We worked together, holding meetings in Ottawa and Toronto; we wrote papers only issued confidentially.

After the war these papers were declassified—that is, they were released for publication and did appear in scientific journals. They were not so very important but still they were not without some value.1

At the same time that we did research on radar there was a group in Montreal working on nuclear physics and the construction of the atomic bomb.2 I was barely aware of this at the time and had no idea how far they had progressed. I had nothing to do with this activity and knew only that one of my students took part in it.

When I was still of school age in Krakow I was deeply impressed by the touching story of the young French mathematician Evariste Galois told me by my old and kindly professor, F. Brablec. I found it extremely dramatic and tragic. The twenty-year-old boy was killed in a duel; on the last night of his life he hastily wrote for posterity the scientific notes from which emerged today's modern algebra. I always {19} wanted to know more about his story. Later, when I was in America working with Einstein, I came upon E. T. Bell's Men of Mathematics.3 It contained sketches of the lives of a number of the greatest mathematicians, including Galois. My interest grew. I decided that some time I would return to this story and learn more about it from original sources. Quite accidentally this came to pass.

One day the editor of my book Quest visited me and proposed that I write a new book, preferably biographical; he suggested in the name of the publishers that it be a life of Copernicus. To tell the truth, Copernicus did not interest me very much. It seemed to me a trivial thing to write so that the English-speaking world would know that Copernicus was a Pole. And I saw little of tragedy in his life. Besides, in America it would be difficult to find original sources. But I recalled my interest in Galois and suggested to the editor that I might try to write the story of his life.

I began to look for sources in Toronto. The university library helped me and so did many American libraries. I found a number of materials previously unknown and uncited, but still many aspects of his life remained unclear. Professor Synge, who knew about my work, told me he had heard that the American millionaire William Marshall Bullitt of Louisville, Kentucky, had collected everything having to do with Galois's life. His agents, through his relative the American Ambassador in Paris, had searched for these documents and he had amassed a unique collection.

I wrote to Mr. Bullitt who, in return, very kindly invited me to visit him for a few days and to examine his collection. This was near the end of the war when I had little war work to do. I accepted his invitation and had my first fairly intimate association with a real American millionaire. I know that it will not be quite nice of me to tell in detail about those few days and how I spent them. It will not be polite of me, for Mr. Bullitt was very hospitable, receiving me very pleasantly. I stayed with him the whole time in his impressive home— occupying two rooms with a bath, surrounded by beautiful portraits of men and women of olden times. I don't know whether these were real or imaginary people.

When I reached Louisville, it was already very warm. The trip was tiring and I arrived worn-out and dirty. When I telephoned to Mr. Bullitt, he asked me to come to the skyscraper which housed his {20} insurance company. There Mr. Bullitt invited me to have a bath in a luxurious bathroom adjoining his office.

“Today,” he said, “we won't work. We'll just eat supper together and then go to the Derby. I have a box there and I've said we're coming.”

We left the office in his high-powered car. He drove and shouted aggressively at anyone who got in his way. The car had license number I. On the way we talked but little since he was old, having passed his eightieth year, and he was a little deaf. Conversation was difficult. He uttered the brilliant words:

“If Galois were alive today and saw this car, what would he say?”

I was tired and to this foolish question gave an equally foolish answer:

“Some things haven't changed.”

“What? What?” asked Mr. Bullitt.

“Some things haven't changed,” I shouted again.

“For instance...?”

I didn't know how to end this silly conversation.

“The fight for freedom,” I answered.

“What? What?”

“The fight for freedom,” I repeated, fully aware that the talk was becoming quite idiotic.

“Oh, yes. You're right. Today, too, we have a fight for freedom against Roosevelt.” This was during the Roosevelt-Dewey campaign.

We reached his home for supper. I remember that he had corn on the cob for the first course. I have since asked many people in America how millionaires eat corn. No one has been able to give me the correct answer. They only knew that millionaires have the cob cut into pieces and that they have two silver prongs to hold them with. But no one seems to know about the special gadget used to loosen the kernels so that they then fall into the mouth like ripe apples from a tree. Each of us had such a gadget made of silver. With the later courses we were offered two small trays with forty condiments, mostly from India, of which I was familiar only with salt and pepper.

After supper we went to the Derby. When we parked the car, Mr. Bullitt had a long talk with the attendant, asking him to place it so that Mr. Bullitt could get it out easily at any moment and so that no other cars would be near it. He said: “If you're good to me, I'll {21} be good to you.” I was sure that these words, repeated several times, meant that the attendant would be highly rewarded. At the least his son would be sent to college and he himself would receive a hundred dollars. Later it turned out that instead of the usual 25-cent fee, the attendant received 50 cents!

In Mr. Bullitt's loge were a number of people. Some were beautiful women—I think his grandchildren. Horses walked about pulling carts, and the people from time to time stood up and applauded, apparently without reason. I had not the least idea what the Derby was all about.

I listened to the women's talk. They were discussing the make of their airplanes, just as the women of the middle class talk about their cars.

After the Derby we returned to the Bullitt house. We looked over his library with its thousands and thousands of volumes. It was a huge library, and truly beautiful. I wanted to find a book to read in bed but there were so many that it was difficult to make a choice. Finally I selected several and went upstairs to sleep. My rooms were furnished with antiques and had portraits on the walls. I still remember that in the bathroom the toilet paper was rose-coloured and perfumed. The window frames creaked so much in the wind that I was unable to sleep in the midst of all the abundance and luxury.

Next day at about eleven in the morning we went to the office. Three of Mr. Bullitt's secretaries stood at attention—one poured water for him, another dropped aspirin into the water, and a third stood ready with a pad and pen. He graciously drank the water with aspirin and dictated a letter, after which all three ladies left. Mr. Bullitt then showed me his library on Galois; I looked over his collection and at the same time heard his telephone conversation. I don't know to whom he was talking but he was saying that somebody else pleased him very much and should have a better position. Then he telephoned to still another person to say that somebody did not please him and should be released from his job. On his huge desk was a whole collection of pencils on each of which was printed, “Vote for Dewey.”

After two days, my work finished, and tired by the millionaire atmosphere, I wanted to go to New York and then to Toronto. Mr. Bullitt asked me how I wished to travel. I answered that I would go by train. He was amazed—why not by plane? At that time it was {22} impossible to get a seat on a plane without reserving it weeks in advance, and even then it might be withdrawn. It was extremely likely that some colonel or other, with priority, would be assigned the seat. I explained this. He replied that he would get a place for me. He phoned someone and a reservation was made immediately. I left by plane. It was actually my first airplane trip. Mr. Bullitt himself took me to the airport and we were ten minutes late—driving madly on the way—in order to show me that the plane would wait especially for him. Even at my departure, I had to witness how important he was.

The trip was wonderful. The plane flew smoothly and the sight of Washington and the Capitol lit up was thrilling.

When I landed in New York after two and a half hours instead of the twenty-four by train, I felt worn out from my stay in Louisville and my first encounter with an American millionaire.

With my book about Galois I had much trouble, mostly because of my own stupidity! Finally it appeared in America and made but little stir.4 Of all the capitalist countries, it had a greater influence, strangely, only in Japan, where it went through two printings. But it was more popular in the socialist countries, especially in Poland and the Soviet Union.

Einstein liked the book. After reading it he sent me the following letter:

I am very much excited over your book on Galois. It is a psychological masterpiece, a convincing historical picture, an expression of love for human greatness which was combined with an exceptionally honest character.

You may submit these remarks, translated into good English, to your publisher for whatever use he may make of them. These are not some casual remarks of mine; I honestly admire your work. I am particularly impressed with the convincing description of the dark background of the story, convincing because of the timelessness of the circumstances of that unusual man. This is what probably made you write the book. I fully understand it.5

While the war was still on, Professor Synge left Canada to take a better position in the United States. He later ended up at the Institute for Advanced Studies in his native Dublin. Our own small department, {23} which had been independent, became part of the Department of Mathematics with Professor [Samuel] Beatty as its head. Since Dean Beatty is important in this story, it would be well to say a few words about him. He was an older man, more an administrator than a mathematician, in general very decent but capable of doing something unfair more through stupidity than bad character. Dean Beatty had little understanding for the scientific work done by those under him. Still, relations between us were good, even very good and sometimes cordial —largely because of his liberal attitude.

I believe that I have considerably more pedagogical than research ability. I was very anxious to use it to build a strong centre of theoretical physics in Toronto. At the time it was the only place in Canada granting a doctorate in that field. During my whole time in Canada it remained the one place that trained theoretical physicists. But no one in Canada cared about it. The Ph.D.s I trained found positions in other Canadian centres or in the United States—never at the University of Toronto. To my urgent request that our group be enlarged, I received the answer from this very rich university: “No, we can't. We haven't the money.” Finally, after long urging, the university agreed to hire the best Ph.D. I had produced in place of someone who had left for the U.S. After he had been with us for a year, a university in the States offered him a salary of $800 a year more. The young physicist then told me that he would gladly remain in Toronto if the university would raise his salary only $200 a year, as evidence that they really wanted him to stay. In spite of every effort to achieve this small increase, the President, Sidney Smith, refused.

Every province in Canada had its own university. The best-known were McGill University in Montreal and the University of Toronto. But the province of Manitoba also had its university at Winnipeg, the capital of the province. During the last days of the academic year, each university invited someone to deliver an address to the students who were graduating. I was sufficiently well known in Canada for the University in Winnipeg to invite me to be the speaker. For my theme I chose the danger inherent in the lack of respect for learning. I said that if the most brilliant people continued to leave Canada for the United States, then, eventually, according to biological laws, the intellectual level in Canada would go down and I added, in jest, “if for thousands of years this trend does not change, then Canada {24} will become a nation of morons.” That very day the local paper carried the headline: “Infeld Predicts Canada to Be Country of Morons.”6

This lack of respect for scientific work, for the position of a professor, was characteristic of Canada and perhaps still more of the United States. It became more and more disturbing to me and I realized that I would not be able to change it. Actually, this situation changed only after the Soviet Union launched its first sputnik.

In New York, during the war, I met Julian Tuwim. His name is known to every child in Poland, but almost unknown outside the country because poetry is very difficult to translate. Many people in Poland, and I among them, regard him as the best Polish poet of our century, and second only to Adam Mickiewicz in all our Romantic literature that so abounded in fine poetry.

Tuwim barely escaped from the Nazis, coming to New York through Rumania, Italy, and France. A degree of friendship developed between us. In any case, speaking for myself, I felt close understanding mixed with admiration, even a sort of worship. In 1945 Tuwim spent his vacation in Toronto. Once when I visited him there, he asked me with great excitement, “Have you heard the latest? Truman has just announced that an atomic bomb has been dropped on a Japanese city, Hiroshima.”

I was speechless. I had no idea that the United States would produce the atomic bomb so quickly and I certainly did not expect that they would drop it on Japan, which was so near defeat.

During the next few months the papers were full of often-repeated slogans and phrases: “The greatest discovery since the discovery of fire! May God permit us to keep the secret! We must guard this secret which only we know! While we keep the secret, we are secure. We must guard against spies who are trying to steal the secret!”

General Roberts, chief of the Manhattan Project, stated that the Russians would discover the secret for themselves only after twenty-five years, and perhaps never.7 No one spoke out seriously in public against this dangerous and silly talk, except for me. It all began with an invitation from a group of professors, including the president of the university, to talk to them about the atomic bomb. I covered the related physics very quickly and then analysed all the idiotic slogans {25} surrounding the bomb. I tried to explain that there was no secret of the atomic bomb, just as there is no secret to being a good husband, just as there are no secret laws of physics. The real secret, I explained, was that the thing was possible, and that circumstance ceased to be a secret with the explosion on Hiroshima. I went on to say that the Soviet Union also had good physicists and, without spying, could construct an atomic bomb after three or at most four years. With this speech I went to many places. I could not accept all the invitations I received to talk about the atomic bomb. I gave my lecture across the length and breadth of Canada, about fifty times. I also wrote a pamphlet about it.8 Often I talked over the radio. I picked up quite a number of amusing incidents as a result. Probably the best is as follows. Once I gave a talk to very wealthy people in Toronto. Following my speech explaining that there was no secret of the atomic bomb, one bright member of the audience asked: “What should we do to keep the secret of the atomic bomb from Russia?”

A growing opposition to me was developing among those who hated what I had to say. If the Soviet Union could really make an atomic bomb in the time I predicted, then how did I know it? Didn't that mean that I had some kind of dangerous contact with them?

This opposition to me swelled in the next five years. Then, when I wanted to accept an invitation to my native land of Poland in 1950, it burst out in open attack. I was accused of wanting to give the secret of the atomic bomb, of which I had no idea, to a country “behind the iron curtain.” As a result, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police dogged my footsteps and those of my family, we were annoyed by vicious telephone calls, and finally the University of Toronto suddenly cancelled my leave of absence to visit Europe. The net effect of all this was that I remained in Poland, where I still am after fifteen years. Thus, in a smaller way, my own life was changed by the explosion over Hiroshima.

Today, twenty years after the event, human beings are dying because of the two bombs dropped in 1945, and still others are existing in a life that is more like death.

Today, twenty years later, the names of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are more alive than they were in 1945 and will remain as a warning to all mankind of the still greater possible terrors that the people of the world must prevent.

| {26} |

|

plate 2. Leopold Inteld in Toronto. |

| {27} |

I remember how, during the war, I had several dreams that kept being repeated. Here is one of them: somewhere in Krakow, in the Kazi-mierz district, I went alone by streetcar in the direction of the Wawel Castle. The buildings were destroyed, ruins lay about and in the distance there was a sort of hill. Another theme—I was in Poland and afraid of the Nazis, running away from them. Or another: murdered bodies, corpses ... among which I suddenly found myself... I fled from torture, of which I was afraid.... After such dreams I woke up soaking wet.

I seriously considered the possibility that after a Nazi victory in Europe Hitler would attack the United States and Canada. I was glad to think that in that case my life would be in my own hands, that at any moment I could commit suicide with my family. A spark of hope arose in me only when the Nazis attacked the Soviet Union. At that time, Professor [Barker] Fairley and I began the Canadian-Soviet Friendship Society. The atmosphere in Canada had changed. The former antagonism had disappeared; everywhere people were talking about the fight put up by the courageous Red Army, about the great Stalin. Even the Canadian Prime Minister9 took part in a large meeting at which the former U.S. Ambassador to the Soviet Union, Joseph Davies, was the chief speaker.

After 1945 relations between Canada and the Soviet Union changed completely, once again. The papers began to carry articles against the Soviet Union until finally in February of 1946 it was suddenly announced that sixteen people had been arrested as Russian spies. How had this come about?

The code clerk of the Soviet Embassy in Canada, Gouzenko, suddenly fell in love with Canadian democracy and to his lover—to this Canadian democracy—he brought a present of a number of coded documents. It appeared from them that there was a spy ring composed of sixteen people. They used aliases in their reports but he claimed that he knew their real names. These sixteen people turned out, for the most part, to be intellectuals—two university professors, several engineers—people who would never have been suspected. For the first time in a Commonwealth country people were sent to jail by purely administrative measures, without the court order required by the Magna Carta, the basis of British justice. More—the Royal Commission formed for the purpose published a report on the investigation, {28} giving all the names and accusations as established facts before any trials had been held. Even after the cases were heard and the courts found some of the accused not guilty, the Commission Report was not withdrawn.10

Among those arrested I found the names of two people I knew well. I had no doubt they were innocent. One, a scientist who was a professor in a Canadian university, was also known in the United States. Not only I but other professors as well, including conservatives and members of the staffs of famous American universities, believed in his innocence and wanted to help him. However, he was suspended because of the accusation until the court found him innocent.11 The second, also a scientist, even after he was found innocent could not find work in Canada and had to go to Europe.12

Progressive Canadians were up in arms. An organization was formed to help secure defence for the accused. However, there were not many who were willing to be active in the organization. Only eight people, including two professors—Fairley and me. We were both at once dubbed “fellow-travellers.” This term, which at first meant those who followed the Communist Party line, later came to mean anyone who did not spend twenty-four hours a day fighting communism.

Our small group collected money (this was fairly easy) for lawyers and to buy space in the papers for explanations of the historical background and the violation of Canadian justice involved in these summary arrests.

After a full month of confinement, the accused were released to await trial. During the trials it became clear that half of them were innocent; the court found no evidence to substantiate the charges. The other half were sentenced to from one to five years in jail—and for actions proving to have quite ridiculous aims. The accused were charged with giving out information concerning chemical explosives. I was amazed that the Soviet Union would be interested in such information. It was still more surprising that the information had ever been a secret from our allies. How could one keep secrets in wartime that concerned chemical explosions? I could have understood if the secrets had been related to the atomic bomb. The whole thing proved a dud.

Later, one of the engineers who was sentenced to two years wrote me every month from prison, that is, every time he was allowed. I had {29} never met him but he knew of my scientific work and asked me for books about physics and for a subject for him to work on. When he left jail he came to me with the work completed. He later published this paper on the theory of antennas, and it was much quoted.13

Late in 1946, Churchill delivered his famous “Fulton speech,” which first employed the term “iron curtain.” This was the official declaration of the cold war.

During the war the Canadian-Soviet Friendship Society held a congress at which I led the scientific session. One of the participants was Vilhjalmur Stefansson, famous Arctic explorer; another was Norbert Wiener, the inventor of cybernetics.

I had met Norbert Wiener when his daughter was a student in Toronto and he came to visit her. He was of my age, short, fat, round-faced, with eyes full of wonder at the external world and what happens in it—a world he saw through thick glasses. He was always ready to talk about himself. His father had been a professor of Russian at Harvard and, if I remember rightly, a Russian Jew. Norbert Wiener entered college when he was only fourteen or fifteen and he had his doctorate when he was nineteen.14 Next he went to Gdttingen, to that Mecca of mathematicians, for further study. Someone told me the following story about his stay there. A lecture he gave on his work was attended by [David] Hilbert, one of the greatest mathematicians of our century. After the seminar, all those present went, as was their weekly custom, to a beer cellar. Hilbert had asked only for beer and two rolls (no one dared order anything else) when [Felix] Klein appeared. Hilbert greeted him with:

“Professor, it's a shame you didn't attend today's seminar.”

Wiener wondered: “Will he add something complimentary about the lecture?”

“We have had many interesting lectures of various kinds, better and worse, but such a bad lecture as today's we've never had before.”

Another of the many stories that circulated about him was this: Once as he was walking on the M.I.T. campus he met one of his assistants and began to converse with him. As they talked they moved about. Before leaving, Wiener asked:

“Where exactly did we meet? In which direction was I heading?”

“Why do you ask?” enquired the puzzled assistant. {30}

“Because only then can I know whether I was on the way to dinner or whether I've already had it.”

Once we met at a scientific meeting in Boston and we talked and talked. He told me about a detective story he wanted to write in which no one would be able to guess the murderer. I only remember that it depended on a clever use of sleighs. We talked until three a.m. When, terribly tired, I left him, he asked me:

“Is there a meeting going on now that I ought to attend?”

I answered him:

“But it's three in the morning. We'll be meeting today at ten o'clock.”

He then gave me the manuscript of his Cybernetics and asked me to read it.15 I took it and when we met at nine for breakfast, he asked me whether I had finished it.

Once when Professor Wiener came to see me in Toronto, he talked rapidly about a book on philosophy that he was writing and about mathematical machines. He said then that it is possible for man to make a machine to which he would not himself be superior in any way. We asked him whether a machine could make up its own problems or plan new tasks. He said with certainty that it could, that a machine could set its own problems and solve them.

Once we invited him to lecture at the University of Toronto. The hall was full. I was a little late and had to sit in the last row where there was still a free place. Wiener came right up to that row and gave his speech into my ear, so that he could not be heard by the audience.

Another time his lecture made a great impression because it was semi-popular. He presented the idea of cybernetics, then a quite new science, in such a fascinating way that we asked him to repeat the lecture in a still more popular way and we invited doctors, engineers, and biologists. Wiener agreed but just before the lecture he told me:

“I'm going to talk about something else today.”

He then began a highly mathematical lecture which could not be understood by a single doctor or biologist—and they had all been especially invited.

When he saw me once in Toronto after a long interval, he came to my room and his first words, even before shaking hands, were: “Planck's Law must be changed!” {31}

He liked to talk in Chinese, a language he said he had learned during a one-year visit to China. And perhaps it really was Chinese!

He was undoubtedly a genius, but not in the same sense as Einstein whose genius was quiet, easy, and slow. Wiener's brain was on fire— everything burned in it, great and small. He should have had several assistants, especially to sort out the important ideas from the silly ones.

Basically, the Polish emigres in Canada divided into two groups. The first was composed of progressives—communists and their sympathizers or non-party people who understood that the future of Poland was necessarily bound up with the Soviet Union. The second group, much larger, was made up of violent opponents of the Soviet Union. I had contact with the first of these and even gave some speeches for Canadian workers of Polish origin. (Recently I received a very pleasant and touching letter from one of them in Toronto who recalled my lecture, now, after twenty years!) I had little to do with the second group. I can only remember meeting two members of it. One had been the Polish consul in Germany and was living in Montreal. He came to Toronto from time to time to see me. He was quite interesting, intelligent, with some sense of humour but full of hatred towards the Soviet Union. He tried to convince me that the Polish army would make its way through the Balkans to Poland and establish a new force—a “third force” between Russia and Germany.

When I wrote to him in Montreal that I was considering signing the Appeal to Reason prepared by Oskar Lange, he came to see me to persuade me not to do so or at least to wait for a month. His argument had the effect of convincing me that I ought to sign at once.16

My experience with the second member of that persuasion, whom I met in Toronto, was less pleasant. He was Professor [Oscar] Halecki, the president of the Polish Academy in exile which included all Polish professors who were outside Poland during the war. When Mr. Halecki came to Toronto to give a lecture, the President of the University, Canon Cody, invited me to dinner with him. Cody was then close to retirement, a Conservative, a former minister of education of the Province of Ontario, and an honorary member of the Academy in Exile. He was easy-going, limited, and at an age when sclerosis begins. At dinner we had a rather stiff conversation and afterwards went to Professor Halecki's lecture. It was technically excellent {32} but so full of hatred for the Soviet Union that I returned home depressed. At once I sent Halecki my resignation from the Academy he led, and I sent copies of my letter to the Canadian press.

At the same time I wrote an objective (or so it seemed to me) article about Poland for the literary monthly Forum.17 In it I defended the Polish raisons d'etat. (This was before the recognition of the People's Republic of Poland by the Canadian government.) A large part, though not all, of this article was reprinted by Izvestia and Pravda in the Soviet Union as well as by many Canadian publications.

Not long after the formation of the People's Republic of Poland, diplomatic relations were established between Poland and Canada. It so happened that I had to lecture in Ottawa on the atomic bomb at the time and made use of the opportunity to contact the Polish representative in Canada, Doctor [Alfred] Fiderkiewicz. The Ministry was located in two rooms in an Ottawa hotel which also served as the Minister's home. We had lunch together and he told me that the Polish treasures—Chrobry's mace, the Arras tapestries, and other priceless relics—were being held in Canada. At first I thought he was joking, but it turned out to be true. But now, as I write this in November 1963, the treasures have at last returned to Poland.

The entire staff of the Ministry turned out for my lecture, and the chairman publicly welcomed the Minister.

The next representative of Poland was Eugeniusz Milnikiel who later became Polish Ambassador in England and whom I still regard as a friend. Minister Milnikiel then proposed to me that I visit Poland for a few weeks. He invited me in the name of the government to lecture at Polish universities and at the same time advise the government on the organization of the study of physics in Poland.

The academic year in Canada is very short—it ends about the fifteenth of April so that, by the end of April, 1949, I could go to war-damaged Europe, for the first time in thirteen years.

I looked upon this trip as a four-week adventure after which I would return to Canada where I would finally be buried. In general I was fond of Canada. It was a plesasant and easy-going country; life there was peaceful, especially for a family with children. We lived in a house with a garden in a suburban district. Life was comfortable; a good school for our children Eric and Joan was close to home. Shopping was easy, much of it done by telephone. I did not dream that I might {33} leave the country, my house and friends who grew in numbers with every passing year. What people there thought about my visit to Poland can best be explained by the comment of one of my colleagues:

“What? You're not afraid to go to Poland? But they won't let you out again!”

“Why?”

“Because you can be useful to them.”

Inasmuch as I will have unpleasant things to relate about Canada, particularly about some of her high officials of the time, I must also speak of the good things. In this connection, I should like to tell my Polish readers how one obtained a passport in Canada. One went either to a bank or to a post office and took a blank. One filled it out. There were very few questions: “When were you born? Where? Are you a Canadian citizen?” There were no questions of the type used in Poland, like “Have you been abroad before?” and “Have you relatives abroad?” Then followed the statement: “Everything written here is true, which I affirm by my signature.” The only other things necessary were a cheque for two dollars (the price of the passport) and photographs. These had to be verified either by a clergyman or a bank director. Why by just those? For such are the privileged ones in the country. Who verifies their photographs I don't know.